In The Courtroom, My Mom Yelled: “She’s a Total Disgrace” — Until The Judge Leaned Forward and said

“SHE IS MENTALLY SICK” my mom screamed in court. I stayed silent. The judge looked at him and asked: “Do you truly have no idea who she is?” Her attorney froze. “Wait… What?” The Judge Leaned Forward and said some thing that make Mom’s face went pale.

Part 1

“She is mentally sick!”

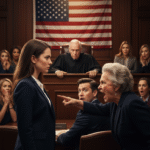

My mother’s voice cracked through Milwaukee County Courtroom 412 like a whip. It wasn’t a tremble. It wasn’t a plea. It was a performance—rage dressed up as concern.

I sat at the respondent’s table on March 14th wearing my grandmother’s pearl earrings and kept my hands folded like I was at church. I didn’t flinch. I didn’t look around to see who was watching. I didn’t even swallow hard.

I stayed silent.

Because I knew something my mother didn’t.

Judge Patricia Kowalchic was the kind of judge who could smell a lie before the sentence finished. Mid-sixties, silver hair pinned neatly back, reading glasses perched low on her nose, her expression practiced neutral—until something didn’t add up. Then her face changed in a subtle, precise way. Like a math teacher catching a student’s fake homework.

My mother’s attorney, Bradley Fenwick, was young—too young to look comfortable in his suit, his tie slightly too wide, his confidence slightly too loud. He’d just finished an opening statement that painted my mother as a worried parent and me as a fragile adult in need of protection.

He called me mentally incompetent.

He said I was unstable.

He said I shouldn’t be allowed to manage my finances, let alone inherit anything from my grandmother.

And when my mother stood and screamed it herself—when she pointed at me like I was a disease—Judge Kowalchic didn’t react with shock. She didn’t scold my mother. She didn’t even raise her eyebrows.

She simply turned to Bradley Fenwick and asked a question in a calm voice that sliced the room in half.

“Counselor,” she said, “do you truly have no idea who this woman is?”

Bradley blinked.

The courtroom went still. Even my mother’s breathing sounded loud.

Bradley looked down at his notes as if the answer might be hiding between his lines. Then he looked at me, then back at the judge.

“I—she’s an accountant, Your Honor,” he said finally. “She works for a firm in Milwaukee.”

Judge Kowalchic held his gaze for a long moment, then glanced at me like she was confirming something she already knew.

My mother’s face shifted from confident to confused to pale in about four seconds.

And that was the exact moment she realized she had walked into the wrong courtroom with the wrong story about the wrong woman.

To understand how we got there, you need to know three things:

My mother abandoned me when I was fourteen.

My grandmother raised me like paper trails were sacred.

And I grew up to make a living exposing people exactly like my mother.

My name is Nancy Bergland. I’m thirty-three. I’m a certified fraud examiner in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. For seven years, I’ve specialized in elder financial abuse—people forging checks, manipulating wills, using fake powers of attorney to siphon seniors dry.

I’ve testified as an expert witness in thirty-eight cases.

Thirty-one convictions.

Eleven times in Judge Kowalchic’s courtroom.

She once said on the record that I was one of the most credible expert witnesses she’d encountered in twenty years.

My mother did not know any of this.

We hadn’t spoken in nineteen years.

When I was fourteen, my parents divorced, and my mother—Daisy Hollister now, Daisy Bergland then—moved on like I was a piece of furniture left behind in the split. She remarried within three months to Theodore Hollister, a man who owned three laundromats and wore charm like cologne.

My mother didn’t fight for custody.

She didn’t call on birthdays.

She sent one Christmas card the first year with my name misspelled and nothing after that.

My father moved to Oregon and started a new life with a new family.

I stayed in Wisconsin with the only person who actually wanted me.

My grandmother, Dorothy Bergland.

Dorothy was a retired elementary school teacher who never made more than forty-two thousand dollars a year. She didn’t own fancy things. She didn’t travel. She didn’t “reinvent herself.”

But she was careful in a way that looked like love.

She balanced her checkbook every Sunday morning with coffee—two sugars, splash of whole milk. She kept receipts in labeled envelopes. She wrote dates and amounts and notes like the future might need proof.

When I was fifteen and angry at the world, she didn’t lecture me about gratitude. She sat beside me and taught me how to reconcile statements because, she said, “When you understand numbers, nobody can confuse you on purpose.”

Eight months ago, Dorothy died peacefully in her sleep. Congestive heart failure. Eighty-one years old. I was holding her hand when her breathing slowed and stopped, and for a few minutes afterward I stayed there, holding on, as if warmth could keep her in the world.

She left me everything.

Her house in Oaklair worth about $285,000.

Her savings—$167,400.

A small life insurance policy.

Not a fortune. But hers. Earned one third-grade spelling test at a time.

Three weeks after her funeral, I received a letter from an attorney named Bradley Fenwick.

My mother was contesting the will.

According to the letter, Daisy Hollister claimed Dorothy had been suffering severe mental decline in her final years. She claimed I had isolated my grandmother. She claimed I manipulated a vulnerable elder into leaving me the entire estate.

The woman who hadn’t visited her mother in fifteen years was accusing me of elder abuse.

I laughed when I read it.

Then I stopped laughing because the letter went further.

My mother had petitioned the court to declare me mentally incompetent and appoint a conservator to manage the estate.

The proposed conservator was, of course, Daisy Hollister.

She didn’t know if my birthday was in March or May.

But she knew the exact dollar amount of Dorothy’s savings down to the cent.

Funny how memory works when money is involved.

Part 2

Once a petition like that gets filed, it doesn’t matter how ridiculous it is.

The system moves anyway.

You don’t get to say, This is nonsense, and walk away. You have to respond. You have to show up. You have to prove you’re not crazy.

And while you’re proving it, people talk.

My firm put me on administrative review within forty-eight hours. Not because they believed my mother, but because credibility is fragile in my line of work. You can’t be the expert witness on other people’s fraud if someone is publicly questioning your mental competency in probate court. Insurance carriers don’t like risk. Neither do juries.

My boss, Harold, called me into his office and looked genuinely uncomfortable.

“Nancy, I believe you,” he said. “But we have to bench you until this is resolved.”

Benched.

No new cases. No testimony. No work that mattered.

Seven years of building my reputation, and my mother took a wrecking ball to it with one attorney letter.

Her “evidence” was creative, I’ll give her that.

As my legal guardian when I was a teenager, her name had been on the intake paperwork for a school counselor. After she abandoned me, I spent about eight months meeting with that counselor because, shockingly, getting discarded by your mother can make a child sad.

The counselor wrote that I struggled with abandonment, low self-worth, adjustment issues.

Normal teenage grief.

Bradley Fenwick presented it as proof of lifelong mental illness.

My mother also produced a signed statement from my stepsister, Merlin Hollister.

Merlin was twenty-eight, Theodore’s daughter from a previous marriage. According to her statement, I’d always seemed unstable and erratic and she had “serious concerns” about my ability to manage finances.

Merlin was nine the last time she saw me.

I hadn’t spoken to her in nineteen years.

She knew nothing about my adulthood, my work, my life. But in court, statements don’t have to be accurate to be harmful. They just have to exist.

Cameron, my boyfriend, took it worse than I did at first.

Cameron Linkfist is a high school history teacher with the kind of family that still has Sunday dinners and photo albums arranged by year. His mother bakes cookies for school functions and writes thank-you notes on stationary that smells faintly of lavender.

He doesn’t understand dysfunction the way I do.

“Just take the psych evaluation,” he said one night, pacing my apartment like the floor might give him answers. “Prove you’re fine and end it.”

“That’s not the point,” I told him.

He frowned. “But it looks bad that you won’t.”

I stared at him. “Do you know what it means to be forced to prove your sanity because someone wants your money?”

He said something about smoke and fire. About how his parents were asking questions. About how he didn’t want to be blindsided.

I asked him to leave.

He left.

That night I sat alone in my kitchen staring at a photo of my grandmother at my college graduation. Dorothy was seventy-three in the picture, smiling like I’d won the Nobel Prize. All I’d done was earn a bachelor’s degree in accounting, but to her, it was everything.

She used to say, “Paper trails don’t lie.”

People can twist truth. People can scream. People can accuse.

But numbers are honest.

Numbers tell you what happened if you know how to read them.

So I decided to read.

I was still listed as a joint holder on Dorothy’s bank account. She added me two years before she died, while she was lucid, sharp, and stubborn.

“For convenience,” she’d said. “So you can help if I ever get too tired.”

I pulled the bank statements for the last two years of her life and built a spreadsheet the way I always do.

Every deposit. Every withdrawal. Every merchant. Every check number.

And that’s when I found the crack in my mother’s story.

In the final eleven months of Dorothy’s life, there were seven cash withdrawals that didn’t match any of her usual patterns.

No pharmacy.

No groceries.

No utility payments.

Just cash.

Ranging from $4,000 to $12,000.

Total: $47,850.

Each withdrawal happened within three days of a documented visit from Daisy Hollister.

My grandmother had begun showing mild cognitive decline about a year before she died—good days and bad days. Misplaced glasses. Forgotten names. Then quoting poetry from memory an hour later.

Not incompetent. But vulnerable.

And my mother knew it.

The woman accusing me of elder abuse had been stealing from her own mother for nearly a year.

I didn’t sleep that night.

I drank coffee until my hands shook and did what I’ve done for seven years: I investigated.

Because if Dorothy taught me anything, it was this:

When someone tries to rewrite your reality, you don’t argue.

You prove.

Part 3

The next weekend, I drove to Oaklair to go through Dorothy’s house again.

I’d already packed her clothes, sorted her books, cleaned out the pantry like grief has chores attached to it. But this time I wasn’t looking for memories. I was looking for gaps.

The house smelled like her: lavender, old books, lemon cleaner, and that specific kind of quiet that only belongs to women who lived alone without being lonely.

I spent three hours going through her filing cabinet, desk drawers, and the cardboard box she kept labeled IMPORTANT that contained everything from insurance policies to recipes.

Then I remembered something I should have remembered immediately.

Her safe deposit box.

Dorothy added me to it five years ago after a break-in scare in the neighborhood. I’d gone with her once and never thought about it again.

I drove to First National Bank of Oaklair and asked to access the box.

The teller didn’t smile. Small-town banks don’t perform friendliness; they perform discretion.

The vault room was cold, fluorescent, quiet.

When the banker slid the box onto the table and left me alone, I opened it expecting jewelry.

I got jewelry, yes—my grandfather’s wedding ring, Dorothy’s modest necklace collection, a few savings bonds.

But underneath, tucked carefully in the back, was a brown leather journal I had never seen before.

Dated entries. Neat handwriting. Dorothy’s voice on paper.

The first entry was fourteen months before her death.

The last entry was six weeks before she passed.

My grandmother had known what was happening.

She had documented everything.

The first entry made my throat close.

Daisy called today after years. Sounded sweet. Said she wanted to reconnect. Said she made mistakes. I don’t trust it. But I am old. People can change.

The next entries got darker.

Daisy visited in August. Asked to borrow $2,000 for an emergency. Dorothy gave it.

Daisy visited in October. Said Theodore was sick. Needed help with medical bills. Dorothy gave $4,000.

Daisy visited in December. Brought Theodore. Asked Dorothy to sign “papers that would make it easier” for them to help manage her finances.

Dorothy wrote: I was foggy today. I signed. I’m not sure what I agreed to.

Two weeks later: Had a good day. Looked at what I signed. It’s power of attorney. Daisy has control. I feel ashamed.

That line nearly broke me.

My grandmother—the strongest woman I knew—was ashamed.

Not just hurt. Ashamed.

She wrote that she didn’t want me to see her as weak. She didn’t want me to know her own daughter had fooled her.

So she didn’t tell me.

She documented.

Every visit.

Every lie.

Every withdrawal.

The last entry was addressed to me directly.

Nancy, I’m sorry. I tried to tell you. I couldn’t find the words. Daisy will come for the money when I’m gone. I want you to have proof. Fight. I know you will win. You are stronger than me. That is why I know.

I sat on the vault room floor and cried until my chest hurt.

Then I wiped my face, stood up, and got to work.

Because Dorothy didn’t write that journal for sympathy.

She wrote it for strategy.

The power of attorney document, it turned out, wasn’t forged in signature.

Dorothy had signed it. Confused. Manipulated.

But the notarization was fake.

The notary stamp belonged to a man named Ray Gustoson, who retired in 2019. The document was dated 2024.

Someone used an old stamp on a new document.

Sloppy.

Obvious.

Felony.

Then I started digging into Theodore Hollister.

And the deeper I looked, the more my stomach turned.

Theodore’s first wife died in 2012. His mother died in 2017.

In both cases, there were questions about estates. In both cases, money disappeared. No charges were filed, but the patterns were there like fingerprints on glass.

Daisy hadn’t married a desperate man.

She’d married a predator.

And Dorothy wasn’t their first victim.

I called my attorney the next morning.

Caroline Jankowski. Fifty-two. Former prosecutor. Sharp enough to slice steel.

I told her everything—the withdrawals, the journal, the fake notarization, Theodore’s history.

Caroline was quiet for a long moment. Then she said, “This isn’t just probate. This is elder exploitation. Wire fraud. Mail fraud. Possibly federal.”

She asked what I wanted.

I told her the truth.

“I want them to walk into court thinking they’ve already won,” I said. “I want them to commit to their lies under oath. Then I want the evidence to speak.”

Caroline’s mouth curved into a small, dangerous smile.

“I hoped you’d say that,” she replied.

We filed my response deliberately bland.

Denied allegations. Affirmed competency. Requested hearing.

No evidence attached.

No counterclaims.

Nothing to tip them off.

Bradley Fenwick called Caroline the next day, confused.

“That’s all she has?” he asked.

Caroline told him I looked forward to court.

He scheduled my deposition.

My mother watched via video link.

I gave them nothing.

Education? “Bachelor’s in accounting.”

Job? “Accountant.”

Mental health history? “Saw a counselor briefly as a teen.”

Short answers. No explanations. No defenses.

I watched my mother’s face in the corner of the screen shift from nervous to pleased as she mistook my restraint for weakness.

She thought I was broken.

She had no idea that the flat, quiet woman in that deposition was a performance.

I’d sat across from embezzlers and money launderers and watched them talk themselves into a corner.

My mother didn’t understand she was doing the same.

Two weeks before the hearing, something unexpected happened.

Merlin Hollister messaged my attorney.

She wanted to meet.

Caroline advised against it. Could be a trap.

But I remembered Merlin’s face on the deposition video—the way her jaw tightened when Theodore’s name was mentioned. The way she looked away when Daisy laughed.

Fear lives in small movements.

I agreed to meet Merlin at a coffee shop halfway between Milwaukee and Oaklair.

Neutral ground.

Merlin arrived looking nothing like the confident statement she’d signed.

She was thin, tired, dark circles under her eyes, nails bitten down to the quick. She ordered black coffee and didn’t touch it.

“I’m sorry,” she said immediately. “About the statement. My dad wrote it. He told me to sign. I didn’t have a choice.”

“What do you mean you didn’t have a choice?” I asked.

Merlin stared at the table. Her fingers touched the inside of her left wrist as she spoke, and I understood without her saying it outright.

Theodore Hollister wasn’t just manipulative.

He was dangerous.

Merlin told me about Theodore’s mother in Pennsylvania, dementia, nursing home, drained accounts, house sold, estate empty.

“The numbers didn’t add up,” Merlin whispered. “I asked once. One time. And… I learned not to ask again.”

She didn’t have to explain further.

I told her if she told the truth under oath, I would make sure prosecutors knew she cooperated.

Merlin nodded, eyes wet, exhausted.

“I don’t want to go down with them,” she said.

That night, for the first time in weeks, I felt something I hadn’t allowed myself to feel.

Hope.

Not just that I would win.

But that Dorothy might get justice too.

Part 4

March 14th arrived gray and cold.

I walked into Milwaukee County Courthouse early because that’s who I am. Navy blazer, simple makeup, hair pulled back. Not there to perform. There to win.

Cameron sat in the back row, quiet and pale, like he’d finally realized my world was sharper than his. Two colleagues from my firm sat beside him—support without questions.

Caroline sat next to me at the respondent’s table with a briefcase full of evidence my mother didn’t know existed.

Daisy arrived fashionably late at 9:02.

She wore a navy blazer and pearl earrings.

My grandmother’s pearl earrings.

Somehow that detail made me angrier than everything else combined.

Theodore walked behind her, face set in practiced concern, nodding solemnly at the judge like he was a respectful citizen instead of a man who treated old women like ATMs.

Merlin came in last and sat behind Daisy’s table, staring at her hands.

Bradley Fenwick looked like a kid in his father’s suit, shuffling papers, checking his phone.

All rise. Judge Patricia Kowalchic entered and took her seat.

She looked at Daisy.

Then she looked at me.

Recognition flickered in her eyes, subtle but clear. She didn’t say anything. She didn’t need to.

Bradley began his opening. Twelve minutes of concerned mother narrative, isolated elder narrative, unstable daughter narrative.

He never mentioned my career. Never researched beyond surface details. Assumed “accountant” meant harmless.

When he finished, Daisy stood to speak.

She started calm, pretending worry.

Then she escalated into a scream.

“She is mentally sick! She is incompetent! She should never be allowed to control finances!”

I stayed silent.

Judge Kowalchic watched the outburst like she’d seen this movie before.

Then she turned to Bradley and asked the question.

“Do you truly have no idea who this woman is?”

Bradley blinked, confused, unprepared.

“She’s an accountant,” he said.

Judge Kowalchic held his gaze, then looked at Caroline.

Caroline stood. She didn’t give a speech. She just said, “Your Honor, we would like to present evidence that reframes the court’s understanding of this case.”

Judge Kowalchic nodded.

Caroline handed packets to the clerk, to Bradley, to the judge.

She started with the bank records.

Seven cash withdrawals. Total $47,850. Each within three days of Daisy’s visits.

Then the power of attorney document.

The notary stamp.

Retirement records proving the notary’s commission ended in 2019. Document dated 2024.

Bradley’s face went pale.

Caroline presented Dorothy’s journal and read selected entries aloud.

My grandmother’s voice filled the courtroom. Not emotional, not dramatic—just precise, dated, and devastating.

Daisy’s face shifted from shock to indignation, not remorse.

Theodore sat very still, a man who recognized when the game was over.

Caroline finished with Theodore’s pattern—previous estates, missing money, reopened questions.

She noted that federal authorities had been notified and an investigation was underway.

When Caroline sat down, the room was silent.

Judge Kowalchic looked at Bradley.

“Response?” she asked.

Bradley stood, swallowed, and asked for a recess.

The judge granted it.

I watched Bradley lean down to whisper in Daisy’s ear. I couldn’t hear the words, but I saw Daisy’s face change.

Confusion.

Then realization.

Then pale fear.

He was telling her who I was.

How many times I’d testified in this very courtroom.

How often I helped put people like her in prison.

Daisy looked at me for the first time in nineteen years like she was actually seeing the woman I’d become.

I didn’t smile.

I didn’t gloat.

I just looked back and waited.

When court resumed, Bradley stood and said his client wished to withdraw the petition.

Judge Kowalchic shook her head.

“Given the evidence,” she said, “I am not prepared to simply dismiss this matter.”

She denied the petition with prejudice.

She referred the case to the district attorney.

She ordered the evidence forwarded to federal investigators.

Then she looked at Bradley again, her tone still calm.

“And counselor,” she said, “I strongly suggest you learn who you’re calling incompetent before you file paperwork in my courtroom.”

It was over in less than two hours.

No dramatic explosion.

Just paper trails, read clearly.

That is how justice actually works.

Part 5

Three days later, the FBI called.

Special Agent Tina Morales had a handshake like a vice grip and eyes that didn’t miss detail.

“We’ve reviewed your evidence package,” she said. “And we pulled Theodore Hollister’s financial history going back fifteen years.”

Patterns I hadn’t even found yet lit up in her investigation like constellations.

Daisy and Theodore were arrested on April 2nd.

Federal charges: wire fraud, mail fraud, financial exploitation of a vulnerable adult.

The indictment was eighteen pages long.

The investigation into Theodore’s mother’s estate was reopened. Forensic accountants found over $200,000 in unexplained transfers in the three years before her death. Geraldine Hollister had owned her home outright, had a healthy pension, had saved carefully her whole life.

By the time she died, there was nothing left.

Theodore had done this to his own mother.

Then he taught Daisy how to do it to mine.

Merlin testified for the prosecution.

In exchange for full cooperation, she received immunity.

I didn’t know if that was fair. I just knew she’d been living under Theodore’s shadow for years, and she finally stepped out.

The trial lasted two weeks. I didn’t attend most of it. I’d already testified in depositions and handed over documentation. I had cases of my own. Old people being drained by relatives who called it help.

But I was there for the verdict.

Daisy Hollister was found guilty on four counts.

Five years in federal prison.

Restitution ordered: $47,850 plus interest and penalties.

Theodore Hollister was found guilty on seven counts.

Six and a half years in a federal facility in Minnesota.

His laundromats were seized and liquidated. The money went to creditors and restitution.

Their house was sold at auction.

The country club membership—revoked months earlier for unpaid dues.

Every piece of the life they built on stolen money was dismantled and scattered.

Two months after Daisy’s sentencing, a letter arrived.

From my mother.

I didn’t open it.

I gave it to Caroline. She read it and said, “Six pages of excuses and self-pity without a single apology.”

“Do you want to respond?” she asked.

“No,” I said.

Some paper trails aren’t worth following.

Dorothy’s estate was settled in July.

I kept the house in Oaklair. I couldn’t sell it. Not because it was an asset—I own my own condo and do fine—but because it was hers. It held her Sunday mornings and her coffee cup and her quiet discipline.

Cameron and I go there some weekends. We drink coffee on the porch where she used to balance her checkbook, and sometimes we sit without talking, letting her house teach us steadiness again.

Cameron apologized properly, eventually.

Not with flowers or speeches. With changed behavior. He showed up in court. He listened. He stopped asking me to be “easy” for other people’s comfort.

In October, he proposed at the Olive Garden on Route 9 in Wauwatosa, where we had our first date. The breadsticks are unlimited and the memories are good. I said yes.

My firm reinstated me the week after the hearing. Harold apologized personally for benching me, even though he’d had to. My first case back was an eighty-four-year-old woman in Kenosha whose nephew stole $89,000 from her retirement account.

We got every penny back.

He got four years.

Some people think revenge is about rage.

It isn’t.

Revenge is balance.

It’s making sure the people who believe they can take whatever they want learn that paper trails have teeth.

My mother thought I was weak because I stayed quiet.

She thought silence meant surrender.

She forgot I was raised by a woman who kept receipts.

And that in a courtroom, receipts speak louder than screams.

Part 6

The first time I slept through the night after the hearing, I woke up angry about it.

Not because I wanted to stay wired, but because my body had been living in fight-or-flight for weeks and it didn’t know what peace was supposed to feel like. I lay there in my Milwaukee apartment listening to the radiator click and the distant sound of a garbage truck, and it hit me in a blunt, ordinary way: my mother had tried to have me declared incompetent in a courtroom where I’d helped put thieves in prison.

And I’d handled it.

Quietly. Cleanly. With paper.

My phone buzzed on the nightstand. A message from Harold, my boss.

Back in the saddle Monday. No more bench. Proud of you.

I stared at the word proud longer than I expected. It wasn’t that I needed it. It was that I hadn’t heard it from a parent in almost two decades.

On Monday, walking into the office felt like walking into a room that had been rearranged while I was gone. People were kind, but careful. Some avoided eye contact because they were embarrassed they’d wondered, even for a second, if my mother’s story could be true. Others hugged me too tightly as if squeezing hard could undo the stress.

Harold called me into his office before lunch. He stood when I walked in, something he didn’t usually do.

“I’m sorry,” he said, direct. “Not for following policy. For letting your mother’s accusation shake anything here at all.”

“It’s a liability business,” I said. “I get it.”

Harold shook his head. “I do too,” he said. “But I also know character. And I should’ve said that louder.”

He slid a folder across his desk. “Kenosha case,” he said. “Eighty-four-year-old. Nephew drained her retirement. She’s scared. She asked for you specifically.”

I opened the folder and felt my brain settle into its natural place—patterns, timelines, transactions that tell the truth if you force them to speak.

“I’ll take it,” I said.

Harold nodded. “One more thing,” he added, and his expression went careful. “There’s been… interest.”

I lifted my eyebrows.

“People talk,” he said. “Your hearing got around. The judge’s referral. The FBI arrests. Reporters love a clean narrative.”

“I don’t,” I said.

“I know,” Harold replied. “But clients might ask. Opposing counsel might bring it up. If you want, we can arrange a public statement. Something simple.”

I thought of my mother’s screaming face, the way she’d used the word sick like a weapon. I thought of the humiliation she’d tried to force me into.

“No statement,” I said. “My work is my statement.”

Harold’s mouth twitched. “That’s what I figured you’d say.”

That week, the Kenosha case snapped into focus faster than most. The nephew had used online access, transferred funds in neat, repeating amounts that looked accidental but weren’t. He’d also been sloppy enough to buy a jet ski on the same day he claimed he “couldn’t afford groceries.”

When I interviewed the victim, her hands shook around her coffee mug.

“I feel stupid,” she whispered.

I heard Dorothy’s voice in my head: Shame is how they keep you quiet.

“You’re not stupid,” I told her. “You’re human. And someone exploited your trust. That’s on them.”

She started crying silently. I handed her a tissue and waited. That’s another thing Dorothy taught me: don’t rush people through pain just because it makes you uncomfortable.

At home, Cameron tried to be steady, but I could see the guilt he carried for doubting me.

He brought groceries without being asked. He washed dishes I didn’t ask him to wash. He hovered like he was trying to earn his way back into trust.

One night, over Thai food that was too spicy, he finally said, “I’m sorry.”

Not just “sorry for what I said,” but the full version.

“I didn’t understand,” he admitted. “I didn’t understand what it means when someone lies about you in an official way. I’ve never lived in that kind of world.”

“I know,” I said.

His eyes were wet. “I made it about what it looked like. And I should’ve made it about you.”

I studied his face, the sincerity, the discomfort of growth. Then I nodded once.

“Don’t do it again,” I said. “That’s the apology.”

Cameron exhaled like he’d been holding his breath. “I won’t.”

A week later, his mother called me directly for the first time.

“Nancy,” she said softly, like she was approaching a frightened animal. “I want to say… I’m sorry for asking Cameron if there was something he didn’t know. I didn’t mean it cruelly. I just—”

“You wanted to protect him,” I finished.

“Yes,” she said, relieved.

“And I want to protect me,” I replied calmly. “So here’s what I need: if you ever have concerns about me, you ask me. Not around me. Not through Cameron. To my face.”

There was a pause. Then she said, “Okay.”

It was the simplest, healthiest family conversation I’d had in my adult life, and it made me almost laugh at the contrast.

That weekend, Cameron and I drove to Oaklair. The house was still empty of Dorothy’s presence in the way grief makes spaces echo, but it also felt steady. Like the floorboards remembered her routines.

We drank coffee on the porch. Two sugars, splash of whole milk. I did it without thinking, then realized what I’d done and had to look away so Cameron wouldn’t see my face.

“You okay?” he asked.

“I’m fine,” I said, which was mostly true.

Then my phone buzzed.

A text from Caroline: Merlin wants to talk again. Says it’s urgent.

I stared at the screen, and that old investigative instinct sharpened.

When predators get exposed, they don’t vanish neatly. They leave debris.

And sometimes the debris is people like Merlin—survivors who have been quiet too long and finally decide to speak.

Part 7

Merlin asked to meet at the same coffee shop as before. Same neutral table by the window. Same black coffee she didn’t touch.

But this time, she didn’t look tired.

She looked terrified.

“I think he’s going to blame me,” she said immediately, voice low.

“Who?” I asked, even though I knew.

“Theodore,” she whispered. “He’s telling his lawyer I did it. That I handled the accounts. That I forged things.”

My stomach tightened. “Did you?”

Merlin shook her head hard. “No,” she said. “I didn’t touch Dorothy’s accounts. I didn’t even have access. But he’s… he’s good at making stories.”

“Yes,” I said. “He is.”

Merlin’s fingers worried the edge of her napkin. “He sent me a letter,” she said. “From jail. He said if I don’t ‘remember things correctly’ in future proceedings, he’ll tell people I’m unstable. Like your mom tried with you.”

There it was. The family tactic: weaponize credibility.

Merlin swallowed. “I don’t want to be a coward. But I also don’t want to be destroyed.”

I leaned forward slightly. “Then we protect you the way you protected Dorothy,” I said. “With documentation.”

Merlin blinked. “How?”

“Start with that letter,” I said. “Give it to Caroline. We’ll add it to the file.”

Merlin’s shoulders trembled. “I didn’t know you’d help me.”

I held her gaze. “You told the truth,” I said. “That matters.”

For the next month, Merlin and I built her safety net the way Dorothy would have: slow, careful, paper-based. Caroline arranged a protective order preventing Theodore from contacting her directly. The FBI already had interest in anything that looked like witness intimidation. Agent Morales didn’t sound surprised when Caroline forwarded the letter.

“We’ll add it,” Morales said, voice calm and cold. “He’s not the first man to try this.”

Merlin also did something that changed her whole posture: she moved.

Not far, but far enough. She found a small apartment in Milwaukee under her own name, opened her own accounts, got a job at a medical billing office—boring, stable, hers.

One evening, she called me in a shaky voice.

“I bought my own groceries,” she said, like she’d just climbed a mountain.

I smiled in my kitchen. “Good,” I said. “That’s how it starts.”

Around that time, my mother’s lawyer tried one last nuisance move. Bradley Fenwick filed a motion requesting return of “personal property” my mother claimed Dorothy had promised her: jewelry, family heirlooms, “sentimental items.”

It wasn’t about sentiment. It was about testing whether she could still pull anything out of Dorothy’s life.

Caroline handled it in one hearing. She brought photographs of Dorothy’s jewelry inventory list—handwritten, dated years earlier, stored in the safe deposit box. Dorothy had literally written: Pearls to Nancy. Wedding ring to Nancy. Daisy receives nothing.

The judge didn’t even look annoyed. She looked bored, which is worse for someone trying to be dramatic.

Motion denied.

Afterward, Caroline glanced at me and said, “Your grandmother would’ve been excellent in court.”

“She was,” I replied. “She just didn’t know it.”

Cameron and I fought less after that. Not because life got easier, but because he learned what I needed when I’m in battle mode: steadiness, not optimism.

One night, when I was sorting evidence for the Kenosha case, Cameron sat across from me at the table and asked, “Do you ever want to see her?”

He didn’t have to say her name.

My mother.

I stared at my laptop for a long moment. “No,” I said.

Cameron nodded, accepting it without argument. “Okay.”

Then he surprised me. “If you ever change your mind,” he said, “I’ll go with you. Not to make it softer. Just to make sure you’re not alone.”

That was the moment I knew he’d finally understood the difference between a comforting fantasy and actual support.

A month later, Merlin texted me a photo.

It was her left wrist.

No bruise. No hand covering it. Just skin in sunlight.

Caption: I’m not touching it anymore when I talk about him. I didn’t even notice until now.

I stared at the message, feeling something like pride—quiet, steady, real.

Justice isn’t always a slam of a gavel.

Sometimes it’s a woman learning her body can stop bracing.

Part 8

The year after the hearing, life didn’t become perfect.

It became honest.

My mother stayed in federal prison. My stepfather stayed in federal prison. Their appeal attempts went nowhere, because appeals hate receipts. The system that had finally worked for Dorothy didn’t suddenly bend for Daisy’s self-pity.

Merlin kept her job. She started therapy. She made friends who didn’t know Theodore and didn’t care about Daisy. Some days she called me just to ask how to cook chicken without drying it out, and I’d laugh because it felt so normal it was almost painful.

My firm offered me a promotion in the fall: lead examiner for elder exploitation cases across three counties. More responsibility, more testimony, more influence.

Harold asked, carefully, “Do you want it? After everything?”

I thought of Dorothy’s journal. The way she’d written, Fight.

“Yes,” I said.

On Sundays, Cameron and I drove to Oaklair more often than we expected. We didn’t renovate the house into something glossy. We didn’t flip it. We didn’t sanitize it into an “investment.”

We kept it steady.

We fixed a leaky gutter. We repainted the porch railing. We planted lavender near the walkway because Dorothy would have liked that, and because it made the air smell like her without making the house feel haunted.

One Sunday morning, I found myself sitting at the kitchen table with coffee the way Dorothy used to—two sugars, splash of whole milk—staring at a blank notebook.

Cameron walked in and paused. “You okay?”

I tapped the notebook. “I’m thinking about starting something,” I said.

“What kind of something?” he asked, sitting across from me.

“A fund,” I said. “Not huge. Not flashy. Just… practical help for seniors who get exploited. Court filing fees. Temporary housing if they’re living with the person stealing from them. Lock changes. Safe deposit boxes. Stuff that keeps people from staying trapped because they can’t afford the first step.”

Cameron’s eyes softened. “That sounds like you,” he said.

“It sounds like her too,” I admitted.

That winter, we started it quietly: The Dorothy Bergland Receipts Fund. Merlin helped with paperwork. Caroline helped structure it legally. Agent Morales even connected us to a local seniors’ advocacy network.

The first person we helped was a seventy-eight-year-old man whose nephew had been siphoning his social security checks. The man was embarrassed, furious, and terrified.

When I told him, “You’re not stupid,” he looked at me like he didn’t believe it.

Then I handed him a folder. “Here’s your paper trail,” I said. “We’re going to make it speak.”

He started crying, slow and silent.

I thought of Dorothy’s shame. I thought of how shame almost kept her from telling me.

I sat with him until he could breathe again.

In October, Cameron proposed the way the transcript told it—at Olive Garden, breadsticks, awkward joy. I said yes, laughing through tears I didn’t bother hiding.

Two months later, on a cold Saturday, we got married in Oaklair in the backyard with twenty people: coworkers, Linda from my firm, Merlin, Caroline, and a few of Cameron’s family members who had learned that love looks like boundaries, not denial.

I wore Dorothy’s pearl earrings.

Not as a symbol of inheritance.

As a symbol of truth.

After the ceremony, Merlin pulled me aside near the lavender bushes.

“I used to think you were lucky,” she admitted quietly. “That you had Dorothy.”

I smiled faintly. “I was.”

Merlin swallowed. “But now I think… you’re lucky you became who you became.”

I stared at her for a moment, then nodded once. “Yeah,” I said. “I am.”

That night, after everyone left and the house went quiet, Cameron and I sat on the porch with coffee and listened to the wind move through trees.

“I keep thinking about your mom’s scream,” Cameron said softly. “How sure she was.”

I watched the dark yard. “That’s the thing about predators,” I said. “They’re always sure until someone checks the math.”

Cameron leaned his shoulder against mine. “And the judge’s question,” he added. “Do you truly have no idea who she is?”

I smiled, small and tired and satisfied.

“She didn’t,” I said. “Not really. She knew the version of me she abandoned.”

I looked down at my pearl earrings and thought of Dorothy balancing her checkbook, writing notes in envelopes, keeping receipts like prayers.

“And she never bothered,” I continued, “to learn who I became.”

I didn’t need revenge anymore.

I had something better.

A life built on proof, steadiness, and people who didn’t confuse screaming with power.

Because in the end, my mother’s scheme collapsed for the simplest reason of all:

She tried to call me incompetent in front of a judge who already knew exactly who I was.

And once the receipts hit the table, there was nowhere left for her lies to stand.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

Leave a Reply