At one dinner, my son-in-law looked at me like a burden and said straight up, “this house isn’t a place to feed extra mouths,” my daughter stayed silent, and I carried my suitcase out the door like an unwanted extra. In a cheap motel, I accidentally read my mother’s diary and discovered a truth hidden my whole life. Three months later, their apartment rent tripled, and a string of strange things began.

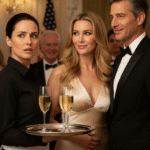

The day I finally let Chad see me again, the community room on the first floor smelled like burned coffee and fresh paint.

Fluorescent lights buzzed overhead. Folding chairs scraped against cheap tile as tenants shuffled in, clutching reusable grocery bags and lukewarm opinions about the new security cameras. A poster about upcoming renovations curled at the corners on the far wall. The property manager fussed with a laptop and a shaky projector, clearing his throat into a microphone that squealed every time he tapped it.

I sat in the last row, legs crossed, hands folded neatly around a legal pad I didn’t actually need. My hair was softer now, styled in loose waves instead of the tired ponytail I’d worn the night my life fell apart. The charcoal blazer I had on fit my shoulders the way nothing had fit me in years. Strong. Intentional. Mine.

Chad barreled in halfway through the manager’s introduction, the way I knew he would. Late, loud, convinced the world would pause until he settled. His baseball cap was pulled low, jaw tight, his old work boots stomping like they owned the floor. Amanda walked behind him, small and folded into herself, eyes on the ground.

He didn’t see me.

Not yet.

He went straight to the front. “I want to talk to whoever thought it was a good idea to triple our rent,” he snapped, voice already raised. “Right now.”

The manager kept his tone even. “All questions will be addressed after the presentation, Mr. Harmon.”

I watched my son‑in‑law bristle under the fluorescent lights he’d once complained made the hallway feel like a hospital. My heart beat a slow, steady drum in my chest.

Three months earlier, he’d told me I was an extra mouth to feed.

Now he was about to find out whose table he’d thrown me away from.

—

People think betrayal feels like a slap.

It doesn’t. It feels like dishes.

It feels like peeling carrots at six in the morning for a dinner nobody asked you to cook but everyone would have judged you for if you hadn’t.

That morning, the one that started it all, I stood at Amanda’s kitchen counter in my old Cedar Park sweatshirt, slicing potatoes into even cubes the way my mother taught me when we still lived in a rented duplex with rattling windows and dreams bigger than the mortgage.

The little rental house Amanda and Chad shared always smelled faintly of last night’s takeout and the citrus cleaner I used after they went to bed. The cheap blinds over the sink rattled when the air kicked on. An H‑E‑B bag sat on the counter, half unpacked, onions rolling lazily toward the stove.

“You don’t have to go all out,” Amanda had said the night before, dropping a frozen pizza on the counter as if that settled the question. “It’s just dinner.”

Just dinner.

For her, it was another Tuesday. For me, it was proof.

Proof that I was still useful. That widows could still matter.

I told myself I was simply filling time. That roasting a chicken, making biscuits from scratch, and baking a peach cobbler was how I kept grief from swallowing me whole. My husband, David, had only been gone a few months. Cancer had taken him slowly, then all at once, the way it does. One morning he’d joked about hospital Jell‑O, and the next his side of the bed was smooth and cold.

We’d built a house together in Cedar Park, north of Austin. We poured our weekends into that place—painting shutters we couldn’t agree on, arguing over backsplash tile at Lowe’s, planting a stubborn oak tree that refused to grow straight. Every nail in that house held a memory. Every creak in the floorboard carried our laughter, our late‑night whispers, our fights about nothing and everything.

After he died, the house turned on me.

The coffee maker gurgling in the morning without his mug beside mine felt like a taunt. The empty recliner in the living room might as well have been a tombstone. I’d walk past his closet, catch the faint smell of his cologne clinging to one last shirt, and end up on the laundry room floor unable to breathe.

So, when Amanda said, “Mom, why don’t you sell the house and stay with us for a while? Just until you figure things out,” it sounded like a lifeline.

I sold the house.

I signed away my front porch, my creaky stairs, the oak tree that finally straightened out when we weren’t looking. I took the equity, paid off lingering medical bills, tucked the rest into a savings account I told myself was a cushion, not a parachute.

And then I moved into a small room at the back of my daughter’s rental, carrying two suitcases and the belief that unconditional love meant you were never really homeless.

—

Chad barely looked up from his phone when I rolled my suitcase down their narrow hallway that first day.

“Hey,” he said, thumbs still moving, eyes still on the screen. “Guest room’s at the back. Amanda, where are my gym shorts?”

I told myself he was distracted. Overworked. That the stiff hug he gave me—a polite tap on the shoulder more than an embrace—was just his way. Not everyone was touchy like David.

Amanda chattered to fill the silence. “You’ll see, Mom. This will be good. We’ll save on your bills, you can help with groceries if you want, and we’ll all be together. Right, Chad?”

He made a noncommittal noise. “Sure. Yeah. We’ll figure it out.”

I took the little room in the back, with its slanted ceiling and view of the neighbor’s fence. I folded my clothes into the cheap dresser someone had left behind. I lined up my shoes in a perfect row and placed our wedding photo on the nightstand. David smiled up at me from behind the dusty glass, forever fifty‑nine, eyes crinkled at the corners.

“I’ll make this work,” I told him.

Because that’s what wives do. That’s what mothers do.

We make it work.

The first week, I tried to be invisible.

I woke up early, before the sun, and made coffee. I washed dishes no one remembered dirtying. I took out the trash, wiped down the counters, and pretended not to hear when Chad sighed loudly every time I opened a cabinet that squeaked.

The second week, I started cooking.

It felt like something I could offer that wasn’t a burden. Meals were my love language. Roasts, soups, casseroles named after church ladies from my childhood. I stocked their fridge with leftovers, labeled neatly in Sharpie.

“Mom, you’re spoiling us,” Amanda said, kissing my cheek. “We’re not used to having real food every night.”

Chad said nothing.

He scraped his plate clean, drank his beer, and scrolled.

By the third week, the comments started.

Little things, at first.

“I can’t find my charger. Did you move it?”

“I like my shirts dried on low. That setting makes them shrink.”

“You don’t have to wipe down the TV, you know. It’s not a museum.”

I apologized. Every time.

“I’m sorry. I was just trying to help.”

He’d shrug, not quite looking at me. “Just… don’t touch my stuff.”

I told myself I was imagining the edge in his voice. That grief made me hypersensitive. That I was reading too much into the way he rolled his eyes if I asked where they kept the aluminum foil.

But then I heard it.

One afternoon, I was in the hallway, folding a load of towels warm from the dryer. The bathroom door was cracked. I heard his voice, low and muttering, the way you talk when you think no one else is listening.

“Forty‑something days of this, and she’s still here,” he grumbled. “Freeloader.”

The word hit harder than any slap.

I stood there holding a towel that smelled like lavender detergent and shame, my throat tight, my ears burning. For a moment I thought I’d misheard. Maybe he’d said “freezer.” Maybe he was complaining about the fridge.

But I knew.

I always knew.

That night at dinner, I looked at Amanda over my mashed potatoes, trying to catch her eye.

“Everything okay?” I asked, when Chad got up to grab another beer.

She smiled too quickly. “Yeah. Why?”

“Nothing,” I lied. “You just seem tired.”

She shrugged. “Work’s rough. Chad’s on a new schedule. We’ll be fine, Mom.”

She said “we” like I wasn’t sitting right there.

It took exactly three months for the illusion of unconditional love to shatter.

—

The night it happened, the kitchen smelled like roasted chicken and rosemary.

I’d made chicken pot pie because it was Chad’s favorite. Some part of me thought if I cooked his favorite meals, he’d see me as something other than a line item on his mental budget.

We sat around the small table. Amanda scrolling. Chad sipping his second beer. The cheap overhead light swaying slightly from the air conditioner kicking on and off.

I tried to make small talk.

“How was work?” I asked.

“Fine,” he said, not looking up.

“Traffic bad on I‑35?”

He exhaled hard through his nose. “It’s Austin, Margaret. Traffic’s always bad.”

Amanda gave me a quick, nervous smile. “Mom, the new HR girl at work brought kolaches today. You would’ve loved them.”

“I could bake some,” I offered. “We could do a whole breakfast spread this weekend. Maybe invite—”

Chad dropped his fork.

The clatter made me jump.

“Can we stop pretending this is normal?” he said.

Amanda’s thumb froze mid‑scroll.

I blinked. “I’m sorry?”

He leaned back in his chair, beer bottle dangling from his fingers. “This. You here. Living in our house like this is some kind of extended vacation. It’s been months.”

My stomach dropped. The room suddenly felt much smaller.

“I’m looking for work,” I said quietly. “It’s just been… hard, with everything that happened with your father‑in‑law, and the market—”

He snorted. “We’re not a charity, Margaret. We didn’t sign up for extra mouths to feed indefinitely.”

Extra mouths.

That phrase lodged in my chest like a shard of glass.

I turned to Amanda.

Surely, she would say something. Surely, my daughter, my only child, the baby I’d rocked through fevers and first dates and college rejections, would draw a line.

“Amanda,” I whispered.

She wouldn’t meet my eyes.

Her fingers twisted the edge of her napkin. “Maybe it would be better if you found something more… stable,” she murmured. “Just for everyone’s sake.”

Everyone’s sake.

The words buzzed in my ears like static.

I stared at her face, trying to find the girl who once cried when I missed a school play because of a double shift at the diner. The teenager who used to curl up on my bed after nightmares, whispering, “Promise you’ll never leave me, Mom.”

She stared at the table.

I didn’t shout.

I didn’t throw my napkin down or overturn the chair or list every single birthday party I’d planned, every pair of jeans I’d hemmed, every time I’d driven across town at midnight because her car “made a weird noise.”

I swallowed.

“Okay,” I said.

I stood up.

I went down the hallway to my small room and pulled my suitcases from under the bed. The same two that had carried my life out of Cedar Park. I folded my clothes with the slow precision of someone performing last rites. I wrapped the wedding photo in a sweater and tucked it between my pajamas.

I didn’t cry while I packed.

I didn’t cry as I walked past the kitchen, dragging the suitcases over the tile.

Amanda pressed herself against the wall as if I were a piece of furniture being moved, not a person leaving.

Chad didn’t look up.

“Thank you for letting me stay,” I heard myself say.

My voice sounded like it belonged to someone else.

No one answered.

I stepped out into the night.

The air was colder than it had any right to be for central Texas. The streetlights hummed. A stray dog barked somewhere down the block. I rolled my suitcases to the curb and sat on one, gripping the handle like an anchor.

The front door closed behind me with a soft click.

Amanda didn’t walk me out.

Chad didn’t pretend to have somewhere to be.

I sat there until my hands went numb.

My phone battery died around the same time hope did.

That was the moment I realized unconditional love has conditions after all.

—

The motel I found that night sat off a service road, tucked behind a gas station that never seemed to close.

The neon vacancy sign flickered in and out, buzzing like a tired mosquito. The lobby smelled like stale coffee and despair. A tired clerk slid a clipboard toward me without looking up from the tiny television playing a game show with the volume too low.

“One night?” he asked.

I hesitated, fingers hovering over my debit card. “For now.”

The room was exactly what the price promised. Peeling wallpaper. A bedspread patterned with flowers that had never existed in nature. A bathroom fan that rattled louder than the passing trucks on the highway.

I set my suitcases down by the door and sat on the edge of the bed.

The springs sighed under my weight.

I stared at the popcorn ceiling until the bumps blurred.

I had given birth in a county hospital with flickering lights and a nurse who called me honey. I had worked double shifts at a diner, rolled silverware at midnight, and smiled through sore feet so Amanda could have new cleats every spring. I had held David’s hand through chemo, through hair loss, through the day the oncologist stopped saying if and started saying when.

But nothing—nothing—prepared me for sitting alone in a motel room with two suitcases and nowhere to go.

I texted Amanda the next morning from the motel’s desktop computer in the lobby, the kind that took forever to load anything.

I’m safe. I understand. I love you.

She didn’t reply.

A week later, I sent another message.

Thinking of you.

Silence.

On her birthday, I sent a heart.

Nothing.

Three months passed.

The motel clerk started greeting me by name. The vending machine became my reluctant roommate, whirring to life every night as I fed it crumpled bills for stale chips and off‑brand soda. I went on interview after interview: front desk jobs, grocery store cashier, receptionist at a dentist’s office that smelled like bubblegum and bleach.

“You’ve been out of the workforce a while,” they’d say, scanning my application.

“I took care of my husband during his illness,” I’d explain.

They’d smile politely, the kind of smile that never reached their eyes.

“We’ll be in touch.”

They never were.

My savings shrank. My hope did too.

Most nights, I lay awake listening to the muffled sounds of late‑night TV from the room next door and the occasional siren wailing down the highway. Grief sat heavy on my chest. Shame curled up beside it.

One evening, when the loneliness felt like a second skin I’d never be able to shed, I pulled the smaller of my two suitcases onto the bed.

It was the one I’d packed last, in a hurry, grabbing the things that felt too precious to leave behind. A shoebox of photographs. The dried corsage from Amanda’s prom, brittle and faded. The plane ticket stub from David’s first work trip to Houston, when we were still young enough to miss each other after one night apart.

At the bottom of the suitcase, wrapped in an old scarf, was a small leather‑bound book.

I didn’t remember packing it.

The cover was cracked at the corners, the leather soft from years of handling. My mother’s old diary.

I’d seen it once when I was a teenager, tucked at the back of her closet. She’d snatched it away before I could open it and said, “Some things are for grown‑up eyes only, Margaret.”

I’d always assumed it was full of grocery lists or prayers she was too shy to say out loud.

Sitting on that motel bed, with the hum of the ancient air conditioner filling the silence, I opened it.

Her handwriting rolled across the pages in neat cursive, loops and swirls I recognized from the notes she used to tuck into my lunch box. At first, it was mundane.

June 12. Church potluck this Sunday. Potato salad turned out too salty. Margaret didn’t notice. Bless her sweet heart.

June 19. The price of sugar keeps going up. Don’t know how we’ll manage if it doesn’t stop.

I smiled, the nostalgia sharp and sweet.

Then, halfway through, the tone shifted.

June 23. He came again today. Said he wished things were different. Said if he were a braver man, he’d put a ring on my finger and his name on our mailbox. But he has a family, a business, a reputation. Said Margaret must never know.

My fingers tightened on the fragile paper.

I flipped forward.

July 2. HJS sent money again. I told him I didn’t want it, but he insists. Says it’s the least he can do for his daughter. I worry. If anyone found out, it would ruin him. It would ruin us. But what choice do I have? Margaret needs shoes for school.

The letters blurred.

I blinked hard.

HJS.

The initials stared back at me from ink that had long since dried.

My heart pounded against my ribs.

I turned more pages, faster now.

September 5. He promised he’d make arrangements. Said if anything ever happened to him, he’d make sure Margaret was taken care of. Nothing official, of course. It’s too dangerous. But there will be a trust. A letter. He said his lawyer, Mr. Goldstein, would know.

I read the entry three times.

Then I whispered the name out loud.

Goldstein.

In a cheap motel off a Texas highway, clutching my mother’s secrets in my trembling hands, I realized two things at once.

First, my life had been smaller than the truth for a very long time.

Second, I had nothing left to lose by chasing it.

—

The motel’s ancient computer groaned as it loaded one search result at a time.

“Goldstein lawyer Texas trust,” I typed, my fingers stiff.

Pages of firms scrolled past. A personal injury attorney in Houston. A tax specialist in El Paso. Finally, tucked halfway down the fourth page, I saw it.

LEONARD GOLDSTEIN, RETIRED ESTATE ATTORNEY – DALLAS, TX.

The phone number looked old, the kind that had been listed in a heavy yellow book once upon a time. I stared at it until the numbers doubled.

I couldn’t bring myself to call.

So I wrote.

On motel stationery that smelled faintly of dust, I wrote a letter in my neatest handwriting.

Dear Mr. Goldstein,

My name is Margaret Louise. My mother was Eleanor Price. I believe you may have known her. I recently found entries in her diary mentioning you and a man with the initials HJS. She wrote that you would know about a trust set aside for me. I don’t know if this is real or if I’m chasing ghosts, but I have nowhere else to turn. If you remember her, if any of this means anything to you, please call me.

I included the motel’s main line and my room number, sealed the envelope, and mailed it from the gas station next door while eighteen‑wheelers rumbled past.

Then I waited.

A week crawled by. Then another.

On the twelfth day, the motel phone rang.

“Room 214,” the clerk called, knocking on my door. “You got a call.”

My legs felt like they belonged to someone else as I walked to the front desk.

“Hello?”

The voice on the other end was thin but sharp. “Is this Margaret Louise?”

“Yes.”

A pause. I could hear paper shuffling.

“This is Leonard Goldstein,” he said. “I’ve been waiting for this call for a very long time.”

I gripped the receiver tighter.

“You knew my mother?”

“Yes,” he said softly. “I knew Eleanor. And I knew… him.”

The way he avoided the name made my stomach flip.

“I think you should come to Dallas,” he continued. “There’s something here that belongs to you.”

—

The Greyhound bus to Dallas smelled like coffee, french fries, and other people’s stories.

I sat near the middle, clutching my purse to my chest, watching scrubby trees and tired billboards blur past the window along I‑35. Rows of highway churches and chain restaurants gave way to overpasses and glass buildings as we approached the city.

Goldstein’s office was in a tired brick building that looked like it had been dignified once. The directory in the foyer listed his name on the third floor, written in a font from another decade.

He met me at the door himself.

He was small and wiry, with a full head of white hair and glasses that slid down his nose when he smiled. Shelves of leather‑bound volumes lined the walls behind him. The place smelled like paper and something older than paper—like history.

“Mrs…?” he began.

“Margaret is fine,” I said.

He nodded. “Margaret.”

He gestured to a chair.

“You look like her,” he murmured, almost to himself. “You have Eleanor’s eyes.”

I swallowed hard. “You got my letter.”

He tapped a thin stack of papers on his desk. “I did. And I dug through boxes I hoped I’d never have to open again.”

From a locked drawer, he pulled out a yellowed envelope, its edges soft, the flap sealed with brittle glue.

My name was on the front.

Not the name my father gave me. The name the man in my mother’s diary had used.

To my daughter, Margaret Louise.

My hands shook as I took it.

“I was instructed to deliver this in the event that you ever contacted me,” Mr. Goldstein said quietly. “I wasn’t allowed to seek you out. Those were the conditions.”

“Whose conditions?” I whispered.

He met my eyes.

“Harold James Sterling,” he said. “Founder of Sterling Energy.”

I knew that name.

Everyone in central Texas did.

His face had been on billboards for decades. Sterling Energy sponsored fireworks shows, charity galas, and high school football stadiums. The Sterlings were local royalty—the kind of family whose weddings ended up in glossy magazines.

My throat went dry.

I opened the envelope.

The letter inside was written in a firm, elegant hand.

Margaret,

If you are reading this, it means I finally did one brave thing in a life full of cowardice.

I am your biological father.

I read the first line three times before my brain accepted it.

He explained everything.

How he met my mother when he was still just Harold from the south side, before the money and the mergers. How they fell in love quietly, desperately, in the gaps between his growing career and a marriage arranged to cement a business deal. How he visited when he could, slipping her envelopes of cash she never asked for, trying to ease the weight he’d placed on her shoulders.

And how, when I was born, he felt a burst of pride he had no right to feel.

I am writing this knowing I will never put my name on your birth certificate, he wrote. I am a coward in that way. But I will do what I can with the tools I have. I have instructed my attorney, Mr. Leonard Goldstein, to see that a portion of my personal, private assets are placed in a trust for you. This will not appear in my will. My family will not know. But you will. Whether you ever forgive me or not, you will at least know this: you were never a mistake to me.

Tears blurred the ink.

Mr. Goldstein pushed a box of tissues toward me without a word.

When I finally looked up, he slid a folder across the desk.

Inside were account statements, trust documents, and a simple summary page.

TOTAL CURRENT VALUE: $1,038,000.00.

A little over one million dollars.

The room tilted.

“This is a mistake,” I said hoarsely.

“It isn’t,” he said. “He set it up quietly, over years. Bonuses, side investments, things his board never knew about. It was his way of carving a space for you in a life he never had the courage to share.”

I stared at the number until it stopped looking like math and started looking like air.

For the first time in months, maybe years, I could breathe without my chest hurting.

“I don’t know what to say,” I whispered.

“You don’t owe anyone words,” Mr. Goldstein replied. “You owe yourself a life.”

That night, back at the motel, I lay on the stiff bed staring at the same textured ceiling.

But everything was different.

My mother’s diary sat open on the nightstand. The letter from Harold rested on my chest. A copy of the trust summary lay beside me, the number one million stamped across the top like a dare.

They had thrown me out with two suitcases.

They had called me an extra mouth.

They had no idea I had a seven‑figure secret in my hands.

For the first time since my husband died, I smiled in the dark.

—

I didn’t go back to Austin right away.

Power is a strange thing when you’ve lived a life without it.

It doesn’t arrive with trumpets. It sits quietly in your lap while you figure out whether you’re allowed to touch it.

I spent a few extra days in Dallas. I walked through neighborhoods where the trees arched over the streets like old friends. I sat in coffee shops with exposed brick and people tapping on laptops, their lives spilling out in email drafts and spreadsheets.

I watched women my age in crisp blazers talk confidently into Bluetooth headphones. I watched young couples argue gently over which couch to buy. I watched teenagers laugh like nothing could ever touch them.

For once, I didn’t feel like a ghost peeking in through a window.

I felt like someone standing just outside a door she finally had a key to.

On the bus back to Austin, I made a promise to myself.

I would never beg for space at someone else’s table again.

Not Amanda’s.

Not Chad’s.

Not anyone’s.

I would build my own.

When I stepped off the bus, I didn’t call a cab to the motel.

I booked a short‑term rental instead, a small furnished apartment just off South Congress. It was nothing fancy—one bedroom, laminate counters, a balky dishwasher—but it was clean and it was mine.

I bought groceries at the nearby H‑E‑B and filled the fridge with fresh vegetables and the cheap yogurt David used to pretend he liked. I hung a mug on a hook by the sink and bought a plant I had no confidence in keeping alive.

Then I opened my laptop and typed “how to invest inheritance” into the search bar.

For weeks, I watched videos about stocks and bonds and real estate. I learned what an LLC was and how leverage worked. I read articles about women starting over at fifty, at sixty, at seventy.

Somewhere between a video on cap rates and a blog about landlord horror stories, I stumbled onto a listing.

MULTIFAMILY PROPERTY – EAST AUSTIN – 12 UNITS – DISTRESSED.

I clicked.

The photos showed a squat, tired building with chipped beige paint and a parking lot full of oil stains. The kind of place you drive past without seeing. The notes mentioned overdue property taxes and an upcoming auction. The starting bid was laughably low for Austin’s market.

The address punched the air out of my lungs.

I knew that building.

I’d dragged my suitcases out of it three months earlier.

Chad and Amanda’s place.

I stared at the screen, my heartbeat thudding in my ears.

Of all the addresses in all of Austin, of all the properties I could have randomly clicked on, it was theirs.

I thought of Chad’s voice in that kitchen, flat and cold.

We didn’t sign up for extra mouths to feed.

I thought of Amanda’s eyes on the table.

Maybe it would be better if you found something more stable.

I thought of the curb, of my numb fingers, of the motel ceiling.

And I thought of the number on the trust summary.

A little over one million dollars.

It felt like the universe had pulled up a chair and said, “Your move.”

—

I didn’t rush into it.

Not because I doubted whether I could, but because I finally understood I didn’t have to do anything from fear anymore.

I called Mr. Goldstein.

“I found a building,” I said.

He chuckled. “Real estate suits you. Send me the listing.”

I emailed it over.

There was a pause on the line long enough for me to hear him adjust his glasses.

“This address,” he said. “Is there a reason it sounds familiar?”

“It’s where my daughter lives,” I replied.

Another pause, this one heavier.

“I see,” he said slowly. “And if you acquired it?”

“They’d have a landlord who knows exactly how thin the walls are,” I answered. “And I’d have an investment that isn’t afraid of me being an extra mouth.”

He didn’t laugh.

But he didn’t say no.

Instead, he walked me through forming an LLC—a simple, anonymous entity: ML Holdings. We filed the paperwork. We transferred a portion of the trust funds.

Two weeks later, I sat in a county building so bland it was almost impressive, clutching a bidder paddle and a folder of pre‑approved payment documents.

The auction was anticlimactic.

A few investors in polo shirts and jeans muttered numbers under their breath. A man in a suit with a coffee stain on his tie yawned. When the auctioneer called the address, only two of us raised paddles. The price climbed, but not high. The overdue taxes and needed repairs scared people off.

My heart hammered as I lifted my paddle for the final time.

The gavel came down with a sharp crack.

“Sold,” the auctioneer called.

Just like that, for a fraction of the million Harold left me, I owned the building my daughter and her husband called home.

I walked out into the bright Texas sunlight feeling taller than I had the day I signed my own mortgage with David.

Back then, I’d built a house.

Now, I held the deed to a whole building.

Three months after they put me on the curb with two suitcases, I owned the roof over their heads.

That wasn’t revenge.

That was gravity.

—

The first thing I did was hire a professional property manager.

I knew enough to know what I didn’t know. I wasn’t going to be the kind of landlord who tried to handle plumbing emergencies with YouTube tutorials.

We walked the property together.

The beige paint looked worse up close. The stair rails wobbled when you leaned on them. A few porch lights were burned out. The landscaping was half dead.

“Tenants mostly pay on time,” the manager said, flipping through a clipboard. “Except Unit 3B. They’re never late, but they’re loud. Complaints about arguments, slammed doors.”

I didn’t need to ask which unit that was.

“Amanda and Chad,” I said.

He glanced at me. “You know them?”

“You could say that.”

We drafted new lease terms—standard, by the book, at market rate.

Most tenants saw modest increases, enough to help cover overdue taxes and planned improvements without pushing anyone out.

For Unit 3B, we adjusted the rent to reflect three months of back under‑market pricing, utilities previously included, and a parking space they weren’t paying for but using.

When the manager read the new figure out loud, he whistled.

“That’s almost triple what they’re paying now.”

I looked at the number.

It wasn’t about the money.

It was about math.

You remove an “extra mouth,” you find out how expensive silence can be.

“Send the notices,” I said.

We mailed official letters on ML Holdings letterhead to every tenant. Rent adjustments. Inspection schedules. Plans for repainting, new lighting, and upgraded security cameras.

Two days later, my phone buzzed.

AMANDA.

I stared at her name on the screen until it stopped ringing.

She left a voicemail.

“Hey, Mom. Um. We just got this letter from our landlord. Our rent went way up. Like… a lot. Chad’s freaking out. I just—are you okay? Can you call me?”

I listened twice.

Then I deleted it.

It wasn’t cruelty.

It was the first boundary I’d ever built that didn’t include a casserole.

A week later, she called again.

“Mom, I know you’re mad. I get it. But things are really hard right now. Chad says there must be some mistake. Can you just talk to me?”

I didn’t answer.

Instead, I walked down to the leasing office and looked at the rent roll.

Amanda and Chad had paid the new amount.

Of course they had.

Chad’s pride would never let him miss a payment. He’d sooner go without groceries than admit defeat.

I didn’t have to imagine how the conversation in their kitchen went.

I’d lived its echo for years.

—

I saw Amanda at the grocery store three weeks after the rent hike.

She didn’t see me.

I was just another woman in the cereal aisle, examining generic brands while fluorescent lights hummed.

Her hair was pulled into a messy bun, strands escaping around her face. There were shadows under her eyes that hadn’t been there the last time I’d seen her up close. Her cart held a few bags of rice, store‑brand pasta, a gallon of milk, and a small pack of chicken thighs.

She picked up a box of mac and cheese, checked the price, then glanced down at her phone.

A text from Chad, probably.

Her shoulders dropped.

She put the box back.

I watched her stand there for a moment, fingers resting on the cart handle like it was the only thing keeping her upright.

For a heartbeat, all I saw was the eight‑year‑old who used to tug on my sleeve in this same store, asking if we could afford the cereal with the cartoon character on the front.

I almost walked over.

Almost.

Instead, I stepped back, letting another shopper cut between us.

Because here’s what no one tells you about being a mother: sometimes the most loving thing you can do is not step in. Not rescue. Not cushion every fall.

I went home and sat at my kitchen table with my mother’s diary open in front of me.

Margaret must never know, the page read.

Well, I knew now.

I knew where I came from.

And I knew I couldn’t keep being the woman who absorbed every blow so other people wouldn’t have to face their own choices.

—

The reports from the property manager became a strange kind of bedtime reading.

“Unit 3B called about the water pressure again,” one email said. “No issue found. Neighbor reports yelling.”

Another time: “Noise complaint filed at 11:47 p.m. Male voice shouting. Female crying. No police called.”

I read them with a knot in my stomach.

This wasn’t what I’d wanted.

I hadn’t bought the building to watch my daughter’s life unravel.

I’d bought it to prove—to myself more than anyone—that I didn’t have to live at the mercy of people who thought I was disposable.

But consequences don’t check intent on their way in the door.

One afternoon, the building manager slid an envelope across the desk toward me.

“Came without a return address,” he said. “Thought you should see it.”

Inside was a single sheet of paper.

I know what you’re doing.

You think you’re clever hiding behind some company name. You think you can push us until we break. But we’re not going anywhere. I’ll find out who you are.

You picked the wrong tenant to mess with.

There was no name at the bottom.

He didn’t need one.

Chad’s handwriting hadn’t improved since the “Happy Mother’s Day” card he’d picked up at a gas station one year when Amanda reminded him.

I held the note between my fingers, the anger rising hot and familiar.

This was the man who’d told me I was an extra mouth to feed while eating the dinner I’d cooked.

This was the man who’d watched me roll two suitcases out into the night and never once asked where I would go.

Now he thought he could haunt me with anonymous threats.

I forwarded the letter to Mr. Goldstein.

“Start a file,” I wrote.

He replied within the hour.

Already done.

—

The first time Amanda came to my new apartment, she buzzed the intercom like a stranger.

“Hi, um… I’m looking for Margaret Louise?” her voice crackled through the small speaker.

I pressed the button to unlock the front door before I could talk myself out of it.

A few minutes later, there was a soft knock.

When I opened the door, she stood there, clutching a canvas grocery bag to her chest like a shield.

Rain beaded on her eyelashes. Her mascara had smudged just enough to make her look younger, like the college kid who used to come home on weekends with laundry and stories.

“Hi, Mom,” she said.

We stared at each other for a long moment.

“Come in,” I said finally.

I poured tea because it gave my hands something to do. Chamomile. The same kind David used to drink when he couldn’t sleep.

Amanda sat on the edge of the couch, fingers wrapped around the mug even though the steam had already faded.

“I don’t know how to start,” she said.

I let the silence stretch.

“He’s not who I thought he was,” she blurted finally. “Chad.”

I lifted my eyebrows.

“I mean, I knew,” she rushed on. “Some part of me always knew. The way he checked my phone, the comments about my coworkers, the way he kept a mental list of everything he did for us. But I told myself he was just stressed. That he just needed support.”

Her shoulders sagged.

“He thinks someone is targeting us now. He’s obsessed with the landlord. Says whoever owns the building is out to get him personally. He’s been digging, calling offices, demanding names.”

I sipped my tea.

“And you?” I asked.

She stared into her mug. “I found your name on a security notice,” she whispered. “The management company sent out a list of properties they handle. This address was on it. I recognized the LLC. ML Holdings. I thought… no. It couldn’t be. But then I remembered your middle name.”

She finally met my eyes.

“Is it you?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said.

She inhaled sharply, like the truth knocked the wind out of her.

“Why?” she asked. “Why would you buy our building and not tell me?”

“Amanda,” I said quietly, “the night I left your house, I didn’t have a plan. I had two suitcases and a motel room that smelled like cigarettes. I found out about Harold, about the trust, when I was counting coins for dinner. I didn’t buy that building to torture you. I bought it because I was tired of living in spaces other people could yank away on a whim.”

Her chin trembled.

“I thought I was protecting us,” she whispered. “Back then. When Chad said… when he said you were an extra mouth. He told me you’d never leave unless we pushed you. He said we were drowning. That we’d lose the house if you stayed. I didn’t want more conflict.”

“You didn’t keep the peace,” I said softly. “You chose a side.”

She flinched like I’d slapped her.

Tears welled in her eyes.

“I know,” she said. “And I hate myself for it.”

I looked at her—really looked at her.

At the girl who used to sit at our Cedar Park kitchen table doing homework while I quizzed her on state capitals. At the woman who had stood silently beside a man who treated her mother like a bill to be cut.

“I missed you,” she whispered. “Every day. I wanted to call. I just… didn’t know how to bridge the space I’d created.”

We sat in silence for a long time.

She didn’t ask for money.

She didn’t ask for a discount on the rent.

She just wanted to sit in a room where no one was shouting.

When she finally stood to leave, she reached for my hand.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “For what I did. For what I didn’t do.”

I didn’t say, “It’s okay.”

Because it wasn’t.

I squeezed her fingers instead.

“That’s a start,” I said.

—

The letter from Chad landed in my inbox two weeks later.

SUBJECT: YOU’RE GOING TO REGRET THIS.

He’d moved past anonymous notes.

He spelled out everything he thought he knew.

I know about Sterling, about your little secret daddy and the million dollars he left you. I know you’re hiding behind that fake company name, jacking up our rent to get back at us. If you don’t roll it back, if you don’t sell this place to someone else, I’ll go public. I’ll tell everyone your mother was a homewrecker and you’re living off hush money. Let’s see how that plays in the news.

The threat might have scared the woman I used to be.

The woman who believed reputations were glass and men like Harold held the only hammers.

But I had a lifetime’s worth of documentation sitting in a file box under my bed. Diaries. Letters. Trust paperwork with signatures older than Amanda.

More importantly, I had Mr. Goldstein.

I forwarded the email.

CALL ME, I wrote.

He did.

“Harassment,” he said, voice clipped. “Defamation. Possibly fraud, if he’s been making misrepresentations to the management staff. We won’t go nuclear unless we have to. But we can make it very, very uncomfortable for him.”

Within days, my attorney—not Goldstein, but a younger woman with a talent for sharp letters—sent Chad a cease‑and‑desist.

It was thick with legal language.

It included printouts of every angry email he’d sent to the property office, every falsified letterhead he’d tried to use to bluff information out of the county clerk, every complaint from neighbors about his shouting.

You are hereby instructed to cease all harassing communications, defamatory statements, and attempts to interfere with the lawful management of the property, it read.

Failure to comply will result in immediate legal action.

The next complaint we got about Chad wasn’t about shouting.

It was about silence.

He’d started disappearing for longer stretches. Coming home late. Leaving early. Amanda’s car stayed in the lot more often. She’d begun walking to work.

I knew because the property manager told me he’d seen her at the bus stop one morning, clutching a travel mug and staring straight ahead.

“She looked… done,” he said.

I nodded.

Done is a sacred place.

It’s where women build exits.

—

The next time Amanda came over, she wasn’t carrying a grocery bag.

She was carrying my mother’s diary.

“I think you left this in my closet,” she said, stepping inside.

Rain pattered softly against the window. Cedar pollen dusted the cars below.

She set the diary on the coffee table like it might break.

“I read it,” she said quickly, before I could speak. “Not all of it. Just… enough.”

Her voice shook.

“I didn’t know about Harold,” she whispered. “Or the trust. Or how hard she fought for you quietly. I didn’t know you spent your whole life not knowing who you really were.”

I sat down across from her.

“I didn’t know either,” I said. “Not until I was sitting in a motel room counting change for dinner.”

She swallowed.

“I left him,” she blurted.

My heart stumbled.

“Chad,” she clarified. “He went through my phone again. My bag. Asked if I was helping you. Accused me of hiding things. I told him no. That I hadn’t spoken to you in weeks. That was a lie. I hated how easy it was to say.”

She lifted her chin, eyes bright with something fierce.

“He packed a bag. Said he was being hunted. Said you were ruining his life. Said he’d be back when I came to my senses.”

“What did you do?” I asked.

“I changed the locks,” she said.

There it was.

The click of a door closing finally in the direction it should have from the start.

“I don’t know who I am without him,” she admitted. “But I’d rather find out than keep disappearing.”

We sat with that for a while.

“I can’t fix what I did to you,” she said. “Kicking you out. Staying silent. Letting him talk about you like you were a line item. I see it now. All of it. It makes me sick. I don’t expect you to forgive me.”

“I don’t know if I can,” I said honestly. “Not yet.”

Her face crumpled.

“But,” I added, “I can choose what we do from here.”

She looked up.

“You see me now,” I said. “Not as an extra mouth. Not as the mom who will always make herself smaller so you can feel bigger. You see me as a woman who owns the building you live in, who built a second life with a million‑dollar secret and a diary full of someone else’s regrets. That changes the story we’re in.”

Her lips parted in a shaky almost‑smile.

“And what story is that?” she asked.

“One where you get to decide who you are without a man telling you,” I said. “And one where I don’t have to disappear to make room.”

—

Selling the building wasn’t dramatic.

It happened on a Tuesday, in a conference room that smelled like printer ink and sugar cookies someone had brought for the staff.

The new buyer was a local investment group that promised to keep the units affordable and the tenants protected. My attorney negotiated a fair price. We signed documents, shook hands, and that was that.

The wire transfer hit my account the next day.

When I looked at the balance, my breath caught.

Between Harold’s original trust and the profit from the sale, the number had climbed. My mother’s secret, my biological father’s guilt, my own stubborn survival—all translated into digits and decimals.

More than one million now.

Enough to build something with.

The first check I wrote was to a local shelter for women and children fleeing domestic abuse and housing insecurity.

The night I left Amanda’s house with two suitcases, I’d had nowhere to go but a motel that took cash and didn’t ask questions.

I wanted other women—the ones whispered about in my building reports, the ones hiding bruises under long sleeves—to have another option.

“We’d be honored to put this toward a new wing,” the director said, eyes wet when she saw the amount. “Is there a name you’d like on it?”

Yes, I thought.

“My mother,” I said. “Eleanor Price.”

ELEANOR HOUSE.

A safe place built on secrets that had finally seen daylight.

The second thing I bought was quieter.

A small two‑bedroom house back in Cedar Park.

Not the one David and I built—that chapter was closed—but a modest place on a tree‑lined street not far from where Amanda learned to ride her bike. It had a front porch with room for a swing, a kitchen big enough for holiday dinners I was no longer willing to cook alone, and a small patch of yard that begged for tomatoes.

The day I moved in, Amanda helped carry boxes.

We didn’t talk much.

We didn’t have to.

She set a box labeled “KITCHEN” on the counter and looked around.

“I remember this neighborhood,” she said softly. “We used to drive through and talk about which houses we’d buy when you and Dad won the lottery.”

“We never did,” I said.

She smiled faintly. “Maybe we just had the wrong ticket.”

We ate grilled cheese and tomato soup that night, sitting on the floor amid half‑unpacked boxes, our backs against the wall.

She burned one side of her sandwich.

“It’s the pan,” she insisted.

“It’s your impatience,” I replied.

We laughed.

Really laughed.

The sound echoed off the bare walls, familiar and brand new at the same time.

Later, after she’d left, I stood at the front window with a cup of tea cooling in my hands.

The street was quiet. A kid rode by on a bike with streamers on the handlebars. Somewhere down the block, someone grilled something that smelled like summer.

I looked at my reflection in the glass.

Fifty‑eight.

Widow.

Daughter of a woman who carried secrets and of a man who finally told one truth on paper.

Mother of a woman who had chosen, belatedly, to change the locks.

Owner of a life that no longer depended on anyone else’s permission.

“I forgive you,” I said.

Not to Amanda.

To myself.

For the years I’d spent begging to be chosen. For the nights I’d convinced myself that being loved meant being useful. For every time I’d stayed silent at a table where people carved up my worth between bites.

I set my tea down and went to the bedroom.

My mother’s diary sat on the nightstand, its leather warmed by the afternoon sun.

I opened it to the last page and slid a small note inside.

Amanda,

If you’re reading this someday, know this: you don’t need anyone’s approval to be worthy. Not mine. Not his. Not theirs. You come from women who survived on secrets and from a man who tried too late to do the right thing. But your story gets to be different.

Don’t ever let someone convince you you’re an extra mouth to feed.

You are the table.

Love,

Mom.

I closed the diary gently.

Some nights, I still remember the curb.

The cold air. The numb fingers. The weight of two suitcases and a lifetime of feeling like a burden.

But then I remember the auction room. The building deed. The million‑dollar trust. The shelter with my mother’s name on it. The little house in Cedar Park with the porch swing that creaks just enough to sound like home.

The woman sitting on that curb thought she’d been erased.

The woman sipping tea by the window knows better.

We’re never erased as long as we keep telling the story.

So that’s mine.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for listening.

Tell me where you’re reading from in the comments. Subscribe if any part of this sounds like a road you’ve walked or might be walking now.

Your story matters.

Your voice isn’t an extra anything.

It’s the one thing no one can evict.

The funny thing is, I didn’t really believe that yet when I wrote it.

I wanted to. I wanted to believe my voice was solid, anchored, something no one could toss out with the recycling. But for a long time, it still felt like something fragile I was borrowing, like a good coat you’re afraid to spill coffee on.

It took a ribbon‑cutting and a cheap microphone in a building that smelled like fresh paint and new beginnings to make it feel real.

—

The day Eleanor House opened, the sky over Austin was that washed‑out blue it gets in early fall, when the worst of the summer heat has finally given up but the air hasn’t remembered how to be cold yet.

The shelter sat on a side street off a busy road, wedged between a strip mall and a little church with a marquee that always seemed a week behind on whatever holiday it was trying to celebrate. The new wing wasn’t big, just a few extra rooms, a common area, a small playroom with a donated rug that looked like a road map.

A banner with my mother’s name hung over the entrance.

ELEANOR HOUSE.

White letters on deep green canvas, flapping slightly in the breeze.

I stood near the back of the small crowd. Staff members in matching T‑shirts. A city councilwoman in a blazer the color of new money. A few donors in pressed chinos. And scattered among them, the women the place was built for, clutching backpacks and diaper bags, standing a little apart like they weren’t sure they were allowed to breathe yet.

The director, a woman named Lila who always smelled faintly of coffee and determination, tapped the microphone, wincing when it squealed.

“Thank you all for being here,” she began. “When we wrote the grant proposal for this wing, we imagined beds, square footage, a bigger pantry. What we didn’t imagine was a donor who understood this place not just on paper, but in her bones.”

She glanced at me.

I looked down at my hands.

“She asked me not to make a fuss,” Lila continued, smiling, “so I won’t. I’ll just say this: Eleanor House exists because one woman decided her worst night wasn’t going to be the end of her story. It was going to be the beginning of someone else’s safety.”

She cut the ribbon with oversized scissors somebody had probably ordered off the internet. People clapped. The councilwoman posed for a photo. A baby somewhere in the crowd started to cry, a thin, insistent wail that sliced through the polite applause.

It was the most honest sound in the whole parking lot.

Inside, the paint still smelled new. The beds were made with matching comforters. There were small baskets on each nightstand with travel‑size shampoo, a new toothbrush, a paperback novel, a notebook.

A notebook.

I ran my fingers over the cardboard cover of one, thinking of my mother’s diary, of ink dried decades ago and secrets that had outlived their shame.

Lila hovered beside me.

“You okay?” she asked softly.

“I’m fine,” I said, then corrected myself. “I’m… full.”

She nodded like she understood.

“Do you want to say something?” she asked. “We’re doing a small circle with the residents in the common room. You don’t have to. But if you want to share why you chose to do this…”

My first instinct was to shake my head.

I’d spent a lifetime being the one who listened while other people talked. Even the million dollars had come with a letter that apologized more than it explained.

But then I saw her.

A woman about Amanda’s age, standing near the doorway of one of the new rooms. She had a toddler balanced on one hip and a bruise fading yellow along her jawline. Her eyes flicked around the hallway like every shadow might be a person.

She caught me looking and tried to smile.

That was it.

That was the moment my voice stopped feeling like something I had to earn and started feeling like something I owed.

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll talk.”

—

We sat in a circle in the common room, on mismatched chairs that had clearly lived other lives before landing here.

A ceiling fan hummed overhead. Somebody had put a plate of store‑bought cookies in the center of the coffee table. It felt like a church basement, or a PTA meeting, except the women here weren’t planning bake sales.

They were planning escapes.

Lila introduced me simply.

“This is Margaret,” she said. “She helped make this wing happen. She’s also… walked a road that might sound familiar.”

I took a breath.

“My daughter kicked me out of her house,” I said.

No warm‑up.

No softening.

A few heads snapped up.

“She didn’t use those exact words,” I went on. “But the message was clear. Her husband stood in the kitchen I’d been cleaning, ate the food I’d cooked, and told me I was an extra mouth to feed. She let him.”

A murmur rippled through the group.

Somebody exhaled sharply.

“I left with two suitcases and nowhere to go,” I said. “I spent a night in a motel off the highway wondering how a woman can give birth to a child and still end up with no one to call.”

The woman with the toddler shifted in her seat.

“What did you do?” one of the others asked.

“I cried,” I said. “Quietly, in a room that smelled like cigarettes and old carpet. Then, eventually, I found out something about where I came from that changed everything. I inherited more money than I ever thought I’d see outside of a lottery ticket.”

Their eyes widened.

“But that’s not the important part,” I added quickly. “The important part is this: the day I realized I didn’t have to beg for space in anyone else’s life again, I stopped trying to make myself smaller.”

I looked around the circle.

“Have you ever stayed somewhere you weren’t wanted,” I asked, “just because the idea of leaving was more terrifying than the pain of staying?”

A few women nodded.

One laughed, a short, bitter sound.

“Every day for six years,” she muttered.

“I bought the building my daughter lives in now,” I said. “The one she watched me walk out of. I became her landlord. It sounds like a revenge story when I say it fast, but it isn’t. It’s a story about gravity. Choices have weight. They come down eventually.”

The women listened like they were drinking.

“I don’t tell you this so you can hope for some secret millionaire in your past,” I said. “I tell you because I want you to hear a woman say out loud that the worst night of her life wasn’t the end. It was a pivot. A hinge.

You can build from the rubble if you stop apologizing for the fact that someone else swung the hammer.”

The room went quiet.

The toddler in the back dropped a toy truck. The clatter echoed.

“Thank you,” Lila said softly.

Later, as I was leaving, the woman with the bruise caught my arm.

“Did your daughter… ever come back?” she asked.

I thought about Amanda on my doorstep, rain in her hair, fear in her eyes, apology on her tongue.

“Yes,” I said. “But not as the woman who kicked me out. As the woman who changed her locks.”

Her eyes filled.

“I don’t know if mine ever will,” she whispered, glancing down at her son.

“You don’t have to know,” I said. “You just have to know who you are when she knocks.”

Her grip tightened for a second.

Then she let go.

Some conversations don’t end in that room.

They just start there.

—

Amanda didn’t come to the opening.

I hadn’t invited her.

That was new for me.

Old Margaret would have sent a text, an address, a little heart emoji at the end.

Come see what I did. Come stand next to me so I can pretend we never shattered.

New Margaret knew better.

You can’t drag someone to your healing and call it reconciliation.

Instead, a few weeks later, she showed up in a different way.

“Do you think they’d take volunteers?” she asked, stirring sugar into her coffee at my Cedar Park kitchen table.

We’d fallen into a rhythm over the past months. She came by once a week after work, sometimes with groceries, sometimes with nothing but tired eyes and stories about HR memos. We didn’t talk about Chad unless she brought him up, which was less and less often.

“For what?” I asked.

She shrugged, looking almost shy.

“I’ve been going to this art class,” she said. “At the community center near my place. It helps. The painting. The mess. The idea that you can put something ugly on a canvas and then decide it’s not ruined, it’s abstract.”

I smiled.

“That’s one way to look at it,” I said.

“They mentioned Eleanor House on a flyer,” she continued. “Said they’re looking for someone to do an art night. For the kids. Maybe the moms. I thought… maybe I could.”

I studied her.

“Is this about making something right with me?” I asked. “Or making something right with yourself?”

She met my eyes.

“Both,” she admitted. “Is that allowed?”

I reached across the table and tapped her knuckles.

“Recovery is buy‑one‑get‑one,” I said. “Sign up.”

She snorted.

“You’re not as funny as you think you are,” she said.

“I’m funnier,” I replied.

We both laughed.

It felt like muscles I hadn’t used in years waking back up.

—

The first night Amanda led art at Eleanor House, I stood in the doorway of the common room and watched.

Someone had dragged folding tables into rough rows. Brown paper covered the surfaces, taped down at the edges. Plastic cups of water sweated rings onto the paper next to cheap brushes and trays of washable paint.

A dozen kids buzzed around the room, voices overlapping like birdsong in a tree that hadn’t decided what season it was.

Amanda wore an old T‑shirt and jeans, her hair in a messy bun. A streak of blue paint already decorated her forearm.

“Okay,” she said, clapping her hands. “Tonight we’re not painting pretty pictures. We’re painting loud ones.”

The kids giggled.

“What’s a loud picture?” a little boy asked.

“It’s a picture that says something you’re not ready to say yet,” Amanda replied. “On paper, you can shout without getting in trouble.”

My throat tightened.

She caught my eye in the doorway and smiled.

“Hi, Mom,” she called. “Grab a brush.”

I walked in slowly.

A few of the mothers were there too, hovering near the back, arms crossed, shoulders tight. Lila nudged one of them gently toward the table.

“Sit,” she whispered. “You’re allowed.”

I sat between a girl who couldn’t have been more than seven and a woman with hollowed‑out cheeks who kept glancing at the exit.

We dipped our brushes in color.

“What are you painting?” Amanda asked, moving between the tables like she’d been doing it her whole life.

The little girl next to me held up her paper.

“It’s a house,” she said. “But the door is really big so my mom can get out when she wants.”

Her mother flinched.

I looked at my own paper.

Without meaning to, I’d painted something that looked suspiciously like a motel room door. Two suitcases sat next to it. The numbers 2‑1‑4 floated above like an address.

Amanda leaned over my shoulder.

“That the motel?” she asked quietly.

“Yes,” I said.

“It looks small,” she observed.

“It was,” I replied. “Back then, it felt like it filled the whole world.”

She nodded, then dipped her brush in a bright yellow and added a small rectangle of light in the corner of my paper.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Your window,” she said. “You couldn’t see it then. But you had one.”

Sometimes healing doesn’t look like a breakthrough.

Sometimes it looks like your grown daughter adding a square of paint to your pain.

—

Life settled into something almost ordinary after that.

Amanda found a small apartment near her job, a studio on the second floor of a building that had no connection to me or Chad or any old ghosts. She bought a secondhand couch off Facebook Marketplace and sent me pictures of it from every angle like she was adopting a dog.

“It sags a little on the left,” she said when I came to see it in person.

“So do I,” I replied. “We can prop each other up.”

She rolled her eyes, but she smiled.

We had dinner together once a week.

Sometimes at my little house in Cedar Park, sometimes at a taco truck halfway between us, once at a noisy chain restaurant off the interstate where the server kept calling us “ladies” and trying to upsell margaritas.

We talked about mundane things.

Her new manager.

My attempt at growing tomatoes.

The neighbor’s dog that had decided my lawn was its personal restroom.

Sometimes, when the conversation lulled, the big things crept in.

“Do you ever hear from him?” I asked one night, meaning Chad.

She shook her head.

“Last I know, he took a job in another state,” she said. “He sent a couple of emails at first. Long ones. Half apologies, half threats. My lawyer told me not to respond.”

“You have a lawyer now?” I asked, surprised.

She grinned.

“I watched you,” she said. “Turns out we’re allowed to have people on our side too.”

Pride swelled in my chest.

Not the kind that puffs you up.

The kind that steadies you.

“Have you ever had to relearn what ‘family’ means,” I asked her, “while sitting across from the person you’re trying to keep and trying not to think about the person you let go?”

She fiddled with her napkin.

“Every time I look at you,” she said softly.

We didn’t rush to fill the silence after that.

Some truths need room.

—

Time has a way of smoothing the sharpest edges without erasing where they cut.

Seasons shifted.

The oak tree in my front yard turned from green to gold to bare and back again. Eleanor House filled and emptied and filled again. Sometimes Lila would call to tell me about a success story—a woman who found a job, an apartment, a new sense of self. Sometimes she called to say nothing more than, “Rough week. Say a prayer if you do that sort of thing.”

Amanda kept showing up for art nights.

Some weeks she came straight from work, still in slacks and flats, swapping her blouse for an old T‑shirt she kept in her trunk. Other weeks she arrived with paint already in her hair from classes at the community center.

I volunteered too, sometimes.

I checked in donations, sorted toiletries, sat at the front desk to greet women who walked in carrying their whole lives in one overstuffed duffel bag.

Every time I saw a woman with suitcases, my chest tightened.

Every time, I reminded myself they were walking into something, not out to a curb.

One evening, close to the anniversary of the night I left Amanda’s place, Lila asked if I’d sit in on a support group.

“Not to lead,” she said. “Just to… be a witness. Sometimes it helps to have someone in the circle who’s further down the road.”

We sat in the same mismatched chairs as the ribbon‑cutting day.

Different faces.

Same hollowed‑out eyes.

A young woman with a baby sleeping on her chest spoke haltingly about the way her mother had told her to “work it out” with the man who’d put her in the ER. Another woman described quietly how her father had told her not to air family business when she’d called asking if she could stay a few nights.

I listened until my heart ached.

When it was my turn to speak, I found myself saying something I hadn’t planned.

“There’s a moment,” I said, “when you realize the people who should have been your softest place to land are the ones pushing you toward the edge. And you have to decide whether you’re going to fall or jump and find out you had wings you never knew about.”

They watched me.

“What would you do,” I asked them gently, “if the person you loved most looked you in the eye and chose someone else’s comfort over your safety?”

No one answered.

They didn’t need to.

They were already living their answers.

—

The last time I saw Chad, it was by accident.

I was in line at a bank downtown, waiting to talk to someone about CDs and interest rates, feeling like a kid playing dress‑up in a grown‑up world.

I heard his voice before I saw him.

“How am I supposed to pay this?” he was saying at one of the desks, loud enough that heads turned. “You people nickel‑and‑dime us and then act surprised when we can’t keep up.”

I froze.

He looked thinner.

Not in a way that made you worry about his health, just… deflated. The swagger he’d worn in Amanda’s kitchen was gone, replaced by a jittery energy that made his leg bounce.

He slammed a stack of papers on the desk.

“Between the lawsuit and the rent and the fees, you’ve bled me dry,” he complained.

The banker kept her voice professional.

“Mr. Harmon, the settlement terms were explained to you. The payment plan is—”

“I know what the plan is,” he snapped. “I’m saying it’s unfair.”

I stepped back, half behind a pillar.

He didn’t see me.

For a moment, I watched him.

The man who’d once held the power to put me on a curb now arguing over overdraft fees.

I didn’t feel triumphant.

I didn’t feel vindicated.

I felt… distant.

Like I was watching a scene from someone else’s life.

I left the line, slipped out the side door, and walked three blocks before I realized I was shaking.

Old fear has a long tail.

When I got home, I made myself tea and sat on the porch swing until the shaking stopped.

The tomatoes in the backyard had finally decided to grow.

I smiled at them like they’d done something miraculous.

Because they had.

—

If you’ve read this far, you’ve walked a lot of miles with me.

From a kitchen in Cedar Park to a motel off the interstate, from a dusty law office in Dallas to a foreclosure auction, from the lobby of a battered apartment building to the quiet halls of a shelter with my mother’s name over the door.

Sometimes I think about the different versions of myself along the way.

The woman peeling potatoes at her daughter’s stove, desperate to be useful.

The woman sitting on a curb with dead phone battery and no plan.

The woman opening a letter worth more than money.

The woman raising a bidder paddle in a room full of men who had no idea who she was.

The woman quietly raising her hand in a support group and saying, “My daughter kicked me out.”

Which version hits you the hardest?

The curb?

The auction room?

The circle at Eleanor House?

Or the moment in my kitchen when Amanda said, “I changed the locks” and meant it in the best possible way?

If you’re reading this on a tiny screen between other people’s posts and perfect pictures, maybe the details of my story don’t match yours.

Maybe you’ve never been kicked out.

Maybe you’ve never found out you were the secret child of a man whose name other people recognize.

But I’d bet there’s at least one moment in your life when you realized the cost of staying quiet was higher than the cost of speaking.

What was the first boundary you ever set with your own family?

Was it saying no to a holiday you didn’t have the bandwidth to host?

Was it moving out when they told you you’d never make it on your own?

Was it blocking a number you used to answer on the first ring?

Or is it still sitting in your throat, waiting for you to trust your own voice?

I can’t tell you what to do.

I won’t pretend my million‑dollar twist is something you can manifest with enough positive thinking.

Life is messier than that.

Crueler, sometimes.

And kinder, in the strangest ways.

What I can tell you is this: the night I stood outside my daughter’s house with two suitcases and nowhere to go, I thought I was nothing more than an extra mouth to feed.

Now I know better.

I was never the extra.

I was the woman who would go on to build a shelter, buy a building, teach another generation how to paint loud pictures and tell louder truths.

If my story is anything, I hope it’s a reminder that you are allowed to take up space.

At your own table.

In your own life.

In your own timeline.

So if you’re here with me, at the end of this long, crooked road, tell me—if you want to, if it feels safe:

Which moment of this story sits with you tonight?

The night on the curb, the letter in Dallas, the landlord reveal in the community room, the paint‑splattered art class, or the quiet forgiveness on a Cedar Park porch?

And what’s one boundary you wish someone had taught you to draw sooner, but you’re willing to sketch out now, even if your hand shakes?

If you feel like sharing, I’ll be the woman in the comments reading every word, nodding along, cheering quietly for strangers I’ll never meet.

Because if there’s anything I’ve learned, it’s this:

When we stop treating our voices like extra mouths and start treating them like the heartbeat of our own stories, we don’t just save ourselves.

We light the way for the next woman standing outside with her suitcases, wondering if she’s worth the key.

Leave a Reply