At Thanksgiving Dinner, My Parents Told Me, “Your Job Is To Work While Your Sister Enjoys Life. Simple As That. If You Have A Problem, There’s The Door.” I Said, “Fine. I’ll Leave, And You Can Start Paying Your Own Bills. Simple As That.”

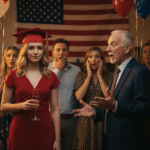

I set the green bean casserole down under the warm glow of the chandelier, Sinatra crooning from Dad’s old Bluetooth speaker, and the smell of roasted turkey and Hatch green chile butter drifting through the adobe house. On the fridge, a faded magnet shaped like the U.S. flag held a dog‑eared acrylic inventory sheet I hadn’t had time to update. My stars‑and‑stripes key fob hung on the hook by the door—habit, muscle memory. Dad didn’t look up from carving. “You missed the acrylic inventory update.” Sawyer swept in late in a camel coat, held a white Hermès Kelly like a trophy, and kissed the air by Mom’s cheek. “Sedona was divine—$3,000 well spent,” Mom beamed. Dad grinned. “How’s the facial princess?” My chest burned. “So I work while she enjoys?” Dad met my eyes without blinking. “Your job is to work while your sister enjoys life. Simple as that. If you don’t like it, there’s the door.” I pushed back my chair. “Fine. I’ll leave, and you can start paying your own bills. Simple as that.”

Numbers don’t lie; people do.

Before I tell you what happened after I grabbed that stars‑and‑stripes key fob and walked out, drop a comment with your city and state—tell me where this lands for you. I’m Carara Finley, 31, an interior designer in Santa Fe, New Mexico. That clash at Thanksgiving wasn’t a lightning strike; it was the last rumble of a storm that started when my hands were too small to carry a gallon of gesso.

I grew up behind our family art‑supply store off Cerrillos Road—the creaky pine floors, the smell of linseed oil and dust, the register bell’s bright ping. At eleven I entered the New Mexico Young Designers Challenge, the one the state AIA ran for kids. I spent nights at the kitchen table sketching a community art center out of recycled pallets and bottle‑brick clerestories, drawing scaled floor plans with a ruler that had belonged to Grandpa Finley. My entry won regional honors and hung at the Roundhouse for a month. I jogged home with the certificate, ready for a photo on the porch steps. Dad skimmed it, dropped it on the counter, and said, “Good. Now finish restocking the watercolor pads before dinner.”

Three months later, my little sister, Sawyer Finley, finger‑painted a sunset on butcher paper in art class. Her teacher sent it home to Mom. Mom framed it, made copies, and hung them in both store locations like we were a chain. That night we piled into the SUV for enchiladas on Cerrillos. Sawyer opened a new iPad loaded with drawing apps. I got extra chores for “distracting the staff with excitement.”

By twelve, chores were a second language. Before school, I restocked acrylic tubes by number; after dinner I scrubbed dried paint off palettes until my knuckles pruned; on trash nights, I dragged bags heavier than I was down the alley. “Sawyer’s busy with her art,” Dad said whenever canvases arrived or brushes needed cleaning. I learned to balance a ladder to touch up the exterior mural—skills no kid should need. Sawyer’s contributions were doodles on scrap paper that Mom laminated and sold as postcards. Customers cooed over her “natural talent” and bought three at a time while my own sketches curled in a drawer like leaves.

When we finally split bedrooms, Dad converted the old storage shed out back for me—bare bulb, cracked concrete, shelves of forgotten sketch pads. Sawyer took the upstairs corner room with the arched window over the cottonwoods. Mom installed track lighting, a drafting table, and a lock “to protect her supplies.” I got a futon and a milk‑crate nightstand.

Weekends meant the register. At fourteen I ran the Saturday shift alone—counted change, wrapped brushes, answered endless questions about oil versus watercolor. Tips went into a jar labeled COLLEGE in Sharpie. Dad praised my reliability within earshot of customers, then handed Sawyer a crisp hundred for markers. She blew it on glitter pens that dried in a week. The pattern hardened like oil paint: I organized the sidewalk sale, designed windows that doubled foot traffic, taught myself inventory software on a secondhand laptop. Sawyer floated through, rearranged a shelf “for inspiration,” and disappeared to sketch at the plaza.

Aunt Violet, Mom’s older sister, saw through the gloss. “That girl’s got two left feet and a silver spoon,” she muttered once, eyes on Sawyer. Mom shushed her. By high school, the back room became my second home. I redrew the layout to fit more easels, negotiated bulk discounts, and built a punch‑card loyalty program that bumped repeat customers 30%. Dad called it “good practice.” Sawyer’s report cards showed C’s in math, but her charcoal portraits snagged blue ribbons at the state fair. Another family outing, green chile cheeseburgers, bowling—whatever she wanted. I absorbed the message: my worth was what I produced; hers was what she dreamed.

I kept adding to the COLLEGE jar, but the weight on my shoulders grew with it. I wanted Savannah College of Art and Design—SCAD felt like a door in a desert wall. So I juggled two part‑time jobs around AP classes. Afternoons, I catered events out in the foothills, balancing trays of hors d’oeuvres while reviewing floor plans on my phone during breaks. Evenings, I did delivery runs for the store three nights a week, Santa Fe’s narrow streets clattering with boxes of spray paint and gesso in the trunk. Every dollar went to application fees, portfolio prints, and—God willing—an enrollment deposit.

Boundaries start as budgets.

Sawyer coasted. Junior year, Mom and Dad made an announcement at dinner—Sawyer would spend a full year studying painting in Florence. All expenses covered. They surprised her with a shiny red Vespa for those cobblestone alleys. “It’s essential for her artistic growth,” Dad said. I did the math: tuition, housing, flights, scooter insurance. My SCAD deposit alone meant another summer of double shifts. I went back to slicing cake at other people’s graduations to fund my own.

Then the pop‑up gallery idea. Sawyer returned from Europe buzzing: a six‑month lease on Canyon Road, custom lighting, imported display cases, her abstracts on white walls. Dad saw “potential” where I saw “math.” They re‑mortgaged the house to bankroll it. Opening night drew a great crowd—wine, compliments, selfies. Sales trickled, then stopped. Suppliers wanted payment for frames and stretchers. After six months there was a $20,000 crater. “Learning curve,” Dad shrugged. I found the refinance paperwork while organizing files for tax season; the new monthly payment jumped $800. Mom explained, gentle as if I were a child, “We needed the equity to give Sawyer a real shot.” I looked at my own student loans—already $30,000, interest compounding—and wired home $1,800 a month from freelance gigs to keep them afloat. I told myself it was for “family stability.”

Acceptance letters came that spring. SCAD offered a partial scholarship but left a canyon‑wide gap. I skipped my own graduation ceremony to work a catering shift. Dad texted, Proud of you for being responsible. Sawyer posted from Tahoe with paintbrush emojis. At SCAD, I lived in a dorm the size of a supply closet, sketched until dawn, interned at firms for credit, and called home to troubleshoot inventory. Sawyer enrolled in community college, withdrew from most classes after the deadline. Mom called it “exploring options.” The store’s profits dipped as online competitors undercut prices, but Dad kept pouring money into Sawyer’s scarf line—a “collection” that never made it past prototypes.

My senior thesis—a sustainable gallery redesign using reclaimed adobe—earned top honors. Professors handed me cards for Atlanta firms. I graduated with honors, $45,000 in debt, and a $52,000 job offer. Sawyer announced her engagement to a photographer she’d met at a workshop. Mom offered the store for the party after hours. The transfer reminders kept hitting my phone. I designed her invitation suite for free and pulled paper from overstock. The wedding cost $15,000, charged to the business account I balanced while my own savings hovered near zero.

No one tracks the cost of being the dependable child until the bill arrives.

Fast‑forward to last Thanksgiving. I’d pulled an all‑nighter redesigning the showroom for the Holiday Rush—modular displays for premium oils, LED strips to spotlight limited‑edition pastels, a flow plan to prevent Black Friday bottlenecks. I also finalized three hotel renderings for a client in Albuquerque—lobby concepts that blended Southwestern textiles with modern minimalism. Time stamps on revisions: 2:30 a.m. I drove to my parents’ place with sleep grit in my eyes and hope gnawing my ribs. Maybe gratitude would soften the edges.

Dad met me at the door with a platter of deviled eggs. “You’re late. New acrylic shipment came in yesterday. Still no inventory update.” I bit my tongue. In the dining room, Mom fussed with cranberry sauce in crystal. Sawyer breezed in, lifted the Kelly bag high. “Look what Mom and Dad surprised me with after my Sedona spa weekend.” Mom glowed. “Your sister needed a reward after closing that influencer deal.” The “deal” was a sponsored post for a crystal shop that barely covered her gas.

I set down the casserole and leveled my voice. “Let me get this straight. I redesign the entire showroom, manage supplier delays, and close six‑figure hotel contracts, and Sawyer gets a luxury bag and a spa retreat for posting pictures?” Dad placed his fork like a gavel. “Your job is to work while your sister enjoys life. Simple as that. If you don’t like it, there’s the door.”

“The door’s that way?” I asked. The chair scraped loud enough to echo off adobe. I took my stars‑and‑stripes key fob from the hook by the fridge, the same hook holding Sawyer’s laminated childhood art. Mom’s voice wavered. “Cara, honey, sit down. We’re grateful.” The tears in her eyes felt rehearsed, the same ones that appeared when Sawyer missed curfew. Sawyer smirked behind her wine. Dad’s face reddened. “After everything we’ve done for you—” His words chased me down the hall, but the porch smelled like pine and cold and November. I slid behind the wheel. The engine drowned out the rest.

I drove twenty minutes south to Drake’s apartment, knuckles white on the wheel. Drake—my boyfriend for two years—opened the door in sweats, eyebrows raised. He didn’t ask. He handed me chamomile and a blanket. We sat quiet until my heart remembered its job. The turkey went cold at their table. I didn’t look back.

Two days later, the first consequence landed. An email from the bank’s loan servicing department: formal notice of intent to foreclose if past‑due mortgage payments weren’t brought current in thirty days. The PDF showed three missed installments totaling just over $5,000 plus late fees. Dad had never mentioned it. I forwarded it to my personal folder, then cut the store’s accounting software off my laptop. The same afternoon the district buyer for Santa Fe Public Schools called me—out of habit. Without updated POs and proof of inventory, they couldn’t renew for spring. That contract—bulk watercolor sets and easels—was worth $12,000. I told her I no longer handled the account. She sounded surprised, then sad.

No is a full financial plan.

The phones started. Dad’s first voicemail at 8:30 a.m.: “You think walking out fixes anything? Get back here and straighten the books before we lose everything.” Slam. Mom followed at 9:41, soft but edged. “My lower back is acting up. I can’t lift the shipments without you. Please call.” Sawyer waited until evening. “Hey, sis. I have a popup paint‑and‑sip idea. Need $10,000 to secure the venue. You’re good with numbers. Wire it over and I’ll pay you back with interest once it takes off.” Delete. Block. I kept my ringtone on vibrate—enough to feel the buzz like a hovering wasp.

Week two, Dad texted photos of overdue utility bills and an empty register drawer. Mom sent links to think pieces about adult children “abandoning” aging parents. Sawyer tried Drake’s phone, her voice breezy about “family investors” and how I was “overreacting.” Drake played it while we ate pasta, then hit delete. By week three, the main supplier put the store on credit hold—no more Golden Artist Colors or Fredrix canvases until the $9,000 balance cleared. Dad called the bank for a short‑term loan and got denied—his credit score had dipped below 600 after the gallery fiasco. He left another message, quieter this time. “The lights stay on because of your spreadsheets. Come fix this.” Mom texted a doctor’s confirmation for her back; the diagnosis was degenerative disc disease—manageable with physical therapy she said she couldn’t afford without insurance co‑pays. Sawyer posted an Instagram Story from the basement: filtered fairy lights, paint‑splattered overalls, captioned “back to basics.” Old friends asked if the store was hiring.

Consequences compound like interest.

A month into silence, Aunt Violet showed up without warning. Southwest red‑eye, rental keys still warm in her hand, she knocked at ten a.m. while I was fielding a materials call for an Albuquerque lobby. I let her in. She set a manila envelope thick with IRS letterhead on my table and slid it across the oak. “They’re drowning,” she said. The notice detailed a $50,000 deficiency from the gallery venture three years back. Dad had inflated deductions—framing, venue rentals, marketing—claiming expenses that never produced revenue. The audit flagged discrepancies between reported losses and actual deposits, added penalties and interest. Violet tapped a line near the end. “Your mom put me as a secondary contact years ago. Bank statements show the mortgage eating 80% of store income. Without your monthly transfers, they’re two payments from default.”

Dad called from the landline that afternoon—first time in weeks. “Violet says you saw the notice. We’re not asking for money. Just one month. Fix the books. Get us through tax season.” Mom clicked onto the speaker, breath catching. “Your aunt agrees. It’s temporary. We’ll pay you consultant rates once cash flow stabilizes.” Sawyer piped in, somewhere between hopeful and entitled, suggesting I could “work remote a few hours a week.” I let them layer the pleas like paint coats, each one meant to cover the last. When they went quiet, I said, “No.”

Numbers don’t heal wounds people keep opening.

That evening I drafted an email from my professional account: subject line—Formal Notice of Financial Separation. I outlined termination of all monetary support, revocation of access to shared accounts, and a request for no further contact on business matters. I attached the bank’s foreclosure PDF as “for reference.” My thumb hovered over send. The stars‑and‑stripes key fob sat beside my laptop, the metal worn smooth where my thumb always pressed. I hit send. Drake leaned against the doorway, arms crossed but eyes kind. He didn’t say “proud.” He didn’t have to.

Sawyer tried Drake again the next day with a pitch for an online watercolor course. He played it on speaker while we ate takeout burritos, then deleted it. Aunt Violet stayed for dinner and told stories about Mom’s failed craft‑fair attempts in the ’80s—the same pattern of grand ideas without the glue of follow‑through. When she hugged me goodbye, she whispered, “You’re not the family ATM. They’ll figure it out, or they won’t.”

The next morning I changed my phone plan and took a new number, forwarding only work contacts. Dad’s final text hit before the switch: a photo of the empty invoice drawer, captioned, “This is on you.” I blocked the thread and snapped the SIM like a match.

Some doors you don’t close—you lock.

Silence fell in layers—first the notifications, then the mental static. Work filled the reclaimed space. I closed out the Albuquerque project and pitched a redesign for El Monte Sagrado in Taos—forty guest suites reimagined with hand‑woven Zapotec rugs, reclaimed piñon beams, and custom vanities inlaid with turquoise. My base went from $92,000 to $129,000 with performance bonuses tied to LEED milestones. Drake hauled boxes up narrow stairs to my new condo—two bedrooms, high adobe ceilings, a corner kiva fireplace, a balcony framing the Sangre de Cristo peaks. Purchase price: $425,000, within reach without gymnastics. He set a ring on my palm—white gold, a single New Mexico turquoise stone he’d sketched himself. My yes felt like steady ground.

Meanwhile, the store’s saga tightened. They sold to a regional franchise out of Albuquerque. The buyer took the inventory at sixty cents on the dollar. After paying the IRS lien—“lien,” not “lean,” a word that sits heavy in your throat—they had $4,300 left. They moved into a one‑bedroom near the Railyard—800 square feet, thin walls, rent capped around $1,550. Dad, sixty‑two, took a night shift with FedEx Ground—10:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m., $21.50 an hour, health insurance after ninety days—something the store had never offered. Mom secured a weekend permit on Canyon Road, propped a folding easel against an adobe wall, and sold 8×10 watercolors of doorways and chile ristras. On strong Saturdays she netted $60 to $120—enough for groceries and the occasional co‑pay. She texted me a photo of her first $50 sale—sunset over the Jemez—but the message bounced back to her inbox: undeliverable.

Sawyer took a job at Hobby Lobby on Cerrillos—starting cashier wage $13.25. Two months of perfect attendance put her in custom framing—measuring matting, assembling shadow boxes for sports jerseys. The 15% employee discount made acrylic sheets and pre‑cut mats cheaper; she started small personal pieces after closing. She enrolled in one evening class at Santa Fe Community College and paid the tuition herself. Her Instagram changed—fewer filtered selfies, more shaky behind‑the‑scenes clips: cutting glass, mixing tints, narrating mistakes. Followers climbed past 3,000. People know real when they see it.

Love isn’t one‑way labor.

I severed the remaining tethers without ceremony—deleted the family Dropbox, removed myself from the vendor portal, filed a change of address at the post office. The final communication traveled certified mail, return receipt requested. I typed one page on firm letterhead. Love isn’t one‑way labor. I wish you growth, but from a distance. This is permanent. The green card came back with Mom’s signature three days later. I slid it into a folder and did not look again.

At the housewarming, we strung lights on the balcony, ladled green chile stew into bowls, and toasted with Gruet from Albuquerque. My portfolio now carried the Albuquerque lobbies and a boutique hotel in Denver; travel pinned itself to our kitchen corkboard—Santa Barbara in spring, Portugal next winter. The mental bandwidth I’d spent on supplier invoices and emergency transfers now fueled mood boards and material samples. Some doors close so you can own the keys.

The stars‑and‑stripes key fob sat in a ceramic dish by my own front door that night, a small relic of a life I no longer owed. I didn’t return it, didn’t keep it out of spite. I kept it as a symbol: I choose which doors I open. Drake squeezed my hand. We clinked glasses with friends and watched the Sangres turn purple.

I didn’t abandon them. I stopped paying for their mistakes. Dad learned punctuality under fluorescent warehouse lights. Mom learned market value one watercolor at a time. Sawyer learned competence with every precise cut of matboard. Consequences taught what indulgence never could.

If this hits home, tell me what you would have done at that table. And if your answer is different from mine, that’s still an answer you owe yourself.

The first ripple hit three weeks after the sale papers cleared. A business columnist from The Santa Fe New Mexican called while I was walking across the Plaza with a roll of finish samples tucked under my arm. “Ms. Finley? We’re running a piece on legacy shops changing hands. Any comment on the art‑supply closure?” I stopped by a bench where a kid in a puffer jacket was feeding pigeons broken crackers. “It didn’t close,” I said. “It changed ownership.” The reporter cleared his throat. “The franchise said their decision was expedited by ‘unsustainable accounting practices under the prior owners.’ That your folks?” I watched the boy laugh as a pigeon hopped onto his shoe. “I won’t talk about my parents,” I said. “I will talk about math. If your story includes numbers, you’ll get closer to the truth than if it includes adjectives.” He chuckled, promised to keep it “clean,” and asked if he could quote me on that last part. “Go ahead.”

Reputations are loud; reality is ledger‑quiet.

Saturday on Canyon Road gave me the second ripple. Drake and I had split a breakfast burrito from Tia Sophia’s and were strolling past galleries when I saw Mom by the adobe wall. Her hair was pulled back with a bandana, her breath puffed in white clouds, her easel angled to catch a doorway’s shadow. A watercolor sunset over the Jemez dried on her board, the same palette she used when we were kids. She spotted me, blinked like she’d seen a ghost, and then lifted a hand. “Cara.”

“Mom.” I kept my voice even. Drake hovered a step back and then gave us space, moving toward a sculpture garden with his hands in his pockets.

Mom adjusted the binder clips on her paper until the silence surrendered. “I sold two pieces last weekend,” she said, nodding toward a cash envelope peeking from a tin. “Sixty dollars Saturday. Eighty on Sunday. It’s… different, earning it.”

“I’m glad,” I said. “How’s your back?”

“Hurts,” she said. “But it’s my hurt to manage.” She glanced at my left hand, at the turquoise ring. Her voice softened. “Congratulations. Drake seems good.”

“He is.” The wind lifted the corner of her tape. I pressed it down. “This one’s nice. Your shadows are better.”

She half‑smiled and looked away. “We weren’t fair to you.”

“We weren’t honest with ourselves,” I said. “There’s a difference.”

She swallowed. “Your father says hi.”

“That’s not a hello. That’s a message.”

She nodded, guilty and small and something else—sturdier, maybe. “He’s… tired. The night shift is a clock that refuses to lie. He says his favorite hour is when the sun hits the loading bay doors. He never noticed that light before.”

“I believe him.”

“I still paint doorways,” she said, a laugh catching on the edge. “Maybe I finally understand them.”

I reached into my tote and handed her a paper cup. “Café au lait from Café Pasqual’s. Too much cinnamon like you like. That’s all I can carry today.”

Her fingers warmed around it. “Thank you.”

“That’s gratitude,” I said. “It’s new on you. It looks good.”

She nodded, eyes glassing but holding. “Happy Thanksgiving early,” she said.

“Happy Thanksgiving,” I answered, and we let the wind finish what we couldn’t.

Boundaries aren’t walls; they’re doors with keys you choose.

A week later Sawyer texted from an unknown number: Can we meet? Just coffee. I stared at the bubbles and the unfamiliar area code but recognized the cadence. Drake raised an eyebrow when I told him. “Public place,” he said. “Clear terms. You’re not a bank.”

We met at Iconik on Guadalupe in the late afternoon when the light in Santa Fe makes everything a movie. Sawyer came in wearing paint‑spattered jeans and a knit beanie, no designer anything, eyes shadowed with actual fatigue instead of filters. She ordered drip coffee and paid with cash. Progress comes in small bills.

“Hi,” she said, wrapping her hands around the cup.

“Hi.”

“You look… good.” Her gaze flicked to my ring and back like she was apologizing for noticing.

“Work’s busy,” I said. “It’s a good busy.”

She nodded, inhaled, and then spoke in a rush. “I owe the framing department two redo’s because I measured wrong by an eighth of an inch. I thought it was nothing, but the client’s jersey would’ve warped. I stayed late and fixed them and didn’t complain because it was my mistake. I haven’t posted about it. I figured I should tell the person who needs to hear it.”

“Good,” I said.

“I’m… trying,” she added. “It’s weird to do the unglamorous parts of art. The measuring, the angles, all the math you always tried to explain.”

“Math doesn’t care if you’re bored,” I said. “It cares if you’re precise.”

She laughed once, then sobered. “I was cruel to you. Not just selfish. Cruel.”

“You were rewarded for pretending life had no receipts,” I said.

She nodded, eyes shining but steady. “I can’t fix everything. But I brought this.” She slid an envelope across the table. I didn’t touch it. “Two hundred dollars,” she said. “It’s what I can do this week. I know it doesn’t cover… anything. But I wanted to start paying back, not with a promise—just money.”

“I don’t accept repayments,” I said. “There’s no ledger you can balance with me that way.”

Her mouth trembled. “Then what do I do?”

“You make exact cuts,” I said. “You show up on time. You stop asking for advances on a future you haven’t earned yet. You build the life you want and you pay for it one shift at a time.”

She nodded hard. “Okay.”

“And Sawyer?”

“Yeah?”

“Don’t spend the $200 to feel absolved,” I said. “Spend it on a square so your lines don’t drift.”

She laughed for real then, hiccup‑bright and clean. “Okay.” She tucked the envelope back into her bag. “I’ve been filming process videos at work. Mistakes and fixes. My followers like the truth.”

“People always have.”

She stood, awkward, younger than her age for a second. “I’m sorry,” she said. “For the door.”

“I’m not,” I said. “I needed it.”

Accountability isn’t an apology; it’s a receipt with a date and amount.

When the El Monte Sagrado kickoff week wrapped, I drove to the Roundhouse on my lunch break. The corridors smelled like floor polish and paper. The receptionist recognized the name of the old youth competition and waved me toward a small conference room where a silver‑haired coordinator named Marisol kept a wall calendar filled with sticky notes. “We’ve shifted funding twice in ten years,” she said, flipping through a binder. “The Young Designers Challenge is still alive, but we’ve lost kids who don’t have gas money or printers.”

“I had a jar labeled COLLEGE in Sharpie,” I said. “It shouldn’t require that.”

“What did you have in mind?” she asked.

“A scholarship that isn’t a photo op,” I said. “No banquets, no podiums. Just coverage for the boring costs that end talent before it starts—foam core, print credits, software licenses, portfolio shipping, travel to juries, meals when you’re too broke to think straight.” I slid a one‑page outline across the table. “Finley Fund for First Drafts. Administered by your office, not by me. Anonymous selection. Five recipients a year. $3,900 each. That’s $19,500. I’ll renew annually.”

Marisol read, smiled, and then sobered. “You don’t want your name attached?”

“I want their names attached,” I said. “I’ll show up for juries if you want another pair of eyes, but I don’t need a picture. I have a job.”

She extended her hand. “Then you just gave a lot of kids a first door.”

I shook it. “Doors are my specialty.”

On the way out, I passed the hallway where my eleven‑year‑old drawing once hung. A third‑grader’s plan for a community art shed sat in its place—crooked labels, fearless colors, the window drawn too big like all hope is. I smiled and took the stairs two at a time.

Invest where proof beats praise.

The franchise that bought the store held a modest reopening. I went because I wanted the goodbye I never got. The new manager, a woman named Letty with a tattoo of a cholla on her forearm, recognized me from the loyalty cards I’d designed a decade ago. “You’re the Finley who did the punch‑card math,” she said, grinning. “We kept it. People love the free brush on the tenth visit.”

“Keep the double‑points during monsoon season,” I said. “Painters restock when it rains.”

Letty laughed. “Already on my calendar.” She lowered her voice. “I heard your folks had a tough run.”

“They did,” I said. “They’re learning.”

“Learning hurts,” she said. “We’re doing free Saturday demos. You should come talk about color temperature.”

“I will,” I said. “On one condition.”

“What’s that?”

“No photos. No ‘hometown hero returns’ headline.”

Letty tapped her temple like we’d made a pact. “We’ll write it on the wall. Invisible ink.”

On my way out I brushed a hand over the old counter, now sanded and oiled, then paused by the hook near the office door where my stars‑and‑stripes key fob used to dangle. The hook sat empty, waiting. I didn’t put anything on it.

Some symbols you keep so you remember; some you leave so you don’t forget.

Thanksgiving came around again fast in a year wired with construction timelines. Drake and I decided on a small dinner—Aunt Violet, two friends from the firm, and the neighbor from across the hall who watered our plants when we were in Taos. We set the table with mismatched plates and linen napkins I bought at an estate sale. Sinatra again, because some rituals can stay.

A knock. I opened the door to find a grocery‑store pumpkin pie sitting on the doormat with a note tucked under the plastic lid. In Dad’s cramped block letters: For your table. No strings. Happy Thanksgiving. I stared at it a long second and then carried it to the kitchen. Drake met my eyes. “What do you want to do?”

“Slice it,” I said. “Feed the people who showed up.”

We ate too much and laughed too loud and clinked glasses to a year that had the dignity to be exactly as hard as it looked. After dessert, Aunt Violet stood with her wineglass and pointed it at me like a gavel. “To Carara,” she said. “Who finally sent the bill back to the right address.”

“Sit down,” I said, embarrassed and grateful.

Violet did not sit. “And to Sawyer,” she added, softer now, “for learning that art without edges is just a mess.” She raised her glass again, to no one in particular. “And to the numbers. May they keep telling the truth.”

After everyone left, I washed plates while Drake dried. He bumped my shoulder with his. “You okay?”

“I’m good,” I said. “I’m better than good. I’m even.”

Even isn’t cold; it’s level.

Two weeks later the reporter’s piece ran—neutral, almost kind. He had called me again to confirm facts and I had made sure the facts were the only thing printed. He used a line I gave him near the end: In small towns, you don’t set fires; you fix wiring. The comments section surprised me—old customers reminiscing about the smell of linseed oil in winter, teenagers who’d bought their first charcoal sticks with babysitting cash, one teacher posting a photo of a classroom set of brushes and a thank you from a decade ago. Underneath, a username I recognized only because it didn’t have a heart emoji: SawyerFFrames. She wrote: We’re open Tuesday to Saturday. If you need matting, I’m measured down to the eighth now. Come by. No hashtags. No filter.

I didn’t click like. I didn’t need to.

Work didn’t slow. Taos wanted site mockups by February, and Denver’s boutique hotel moved their lobby install up a month after a snowstorm delayed the millwork delivery and then miraculously freed all the trades at once. I logged miles, not moods. On a late flight back from DIA the plane banked low over Santa Fe and traced a line of headlights on Cerrillos like a string of beads. Drake slept on my shoulder, his breath warm, his hand anchored on my palm. I thought of every hour I’d ever worked so someone else could have a softer landing and then I thought of my landing—firm because I laid it myself.

The Monday after, Marisol emailed from the Roundhouse with a list of the first five Finley Fund recipients. No names, just initials and line items: J.T., foam core and transit to jury, $218; M.R., portfolio prints and Adobe license, $412; A.K., hotel for two nights during state final, $286; S.P., meals and gas across two counties, $175; L.Y., shipping costs to Austin, $234. At the bottom: Remaining balance held for next cycle, $18,175. I read it twice and smiled until my cheeks hurt.

Satisfaction is compound interest in a life you own.

In March, Sawyer texted a photo. No caption. A framed piece on a neutral wall: a grid of tiny paper samples hand‑tinted with slight shifts in ultramarine. In the corner, the smallest square was labeled “almost.” I typed and erased three different responses before settling on two words: Nice work. The dots danced. Thanks, she wrote. Then: I got into a second class. Design basics. They’re making me learn ratios. You’d like it. I let it sit. Then: Keep going, I replied. A minute later, a final bubble: I am.

Mom and Dad’s apartment near the Railyard didn’t change much on the outside, but the inside did in ways no paper can show. Violet sent me a picture once of Dad’s boots lined by the door like soldiers set at ease and Mom’s paint water in a mason jar with the brush handles pointing up instead of slumped sideways. Small, precise. Learned.

Spring bled into summer, and the Sangres turned the exact pink you’d fight to capture on paper and never could. Drake and I hiked above Tesuque on a morning with air so clear it felt like a promise. At a rocky overlook he took the stars‑and‑stripes key fob from my pocket and dangled it. “You still carry this heavy little thing,” he said.

“It opens nothing,” I said. “It reminds me of everything.”

He hooked it on my belt loop and tugged me close. “Keep it,” he said. “But let it be lighter.”

We stayed there until the sun started to bully the day and then we headed down, our steps steady, our pace matched, the trail ours in both directions.

I didn’t rewrite my family. I revised my role. I didn’t torch the store. I turned off a valve I never had to open. And when the bill for the years came due, I sent it back to the right address with a note: Paid by the lesson, not by me.

If you’re at a table where your worth is counted in chores and silence, here’s the sentence that flips the ledger. It isn’t loud. It doesn’t need witnesses. It’s the sentence I said and then lived: No. And then the one that followed: I’m done. Between them sits a door with a flag key fob and a choice. The math will take care of the rest.