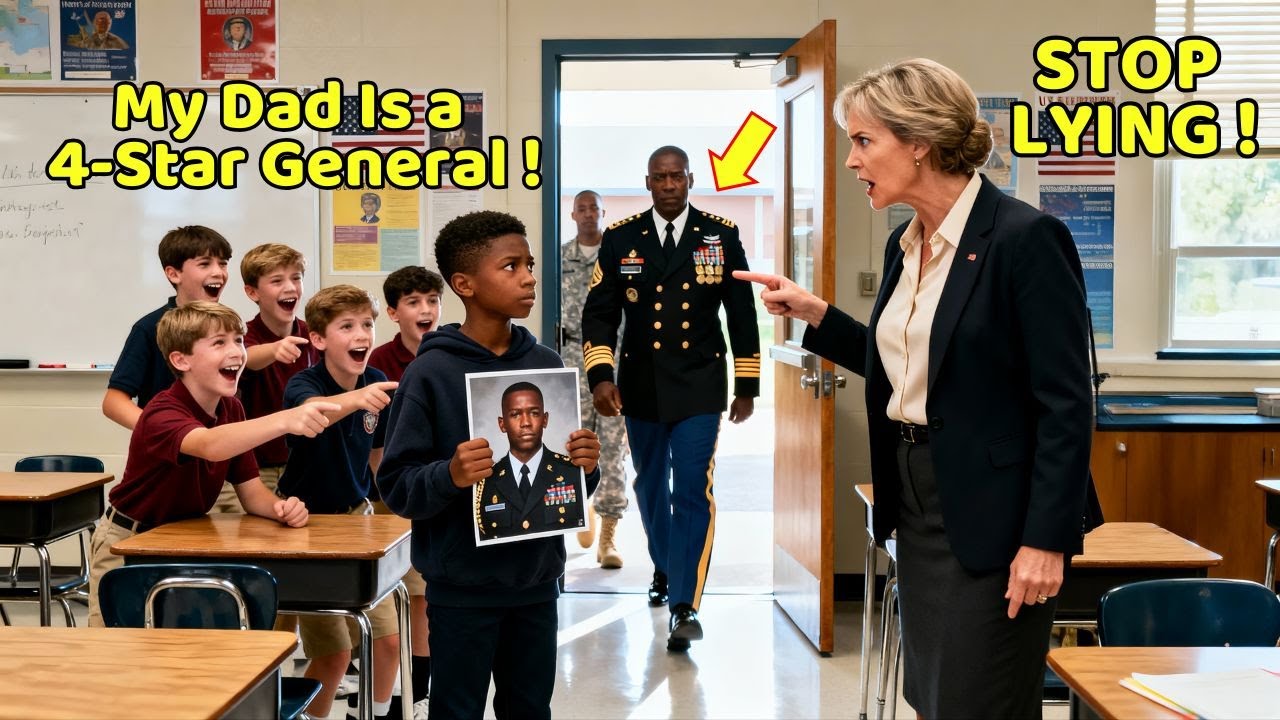

Teacher Rips Up Black Boy’s: ‘Your Dad Can’t Be a General’ — Freezes When 4-Star General Walked In

a fourstar general. Mrs. Henderson’s voice drips with mockery as she holds up James poster. Class, this is what we call pathological lying. Jame, do you think we’re stupid? Do you think I don’t know there are only nine four-star generals in the entire United States? She rips the poster in half, then quarters it.

The pieces scatter across the floor. I can call him right now, Mrs. Henderson. James voice is quiet, steady. He’s at the Pentagon this week. I can prove enough. She drops the torn pieces at his feet. This is stolen valor, a federal crime. I’ve been teaching 15 years, and I know when students exaggerate to get attention. People from neighborhoods like yours don’t just become four-star generals.

28 seventh graders stare. Some smirk. Most look down. Jame bends to pick up the pieces of his father’s face. Have you ever been told your truth was a lie because of how you looked? 3 hours earlier, Jame Washington had walked into Jefferson Middle School with his poster board carefully wrapped in plastic, protecting it from the morning drizzle.

He’d spent two weeks on it. Every detail mattered. The Pentagon insignia printed in full color. His father’s official photo in dress uniform. The four stars on each shoulder gleaming under studio lights. A timeline of his dad’s deployments. Iraq, Afghanistan, Germany, South Korea. 28 years of service condensed into a trifold presentation board.

His mother had helped him last night, her nursing scrubs still on after a 12-hour shift at Community General. Sarah Washington had looked at the poster with tired but proud eyes. It’s beautiful, baby. She’d traced her finger over the photo of her husband. Your daddy’s going to love this. You think Mrs. Henderson will like it? Jame had asked.

Sarah’s smile had faltered for just a moment. Just tell the truth, Jame. That’s all you can ever do. Tell your truth and stand in it. Now, picking up the shredded pieces of that truth from the classroom floor, Jame understands what his mother’s hesitation meant. This isn’t the first time Mrs. Henderson has looked at him like he’s lying.

It’s just the first time she’s been this public about it. Two months ago, she’d pulled him aside after class. Jame, these shoes. She’d pointed at his Air Force Ones, a gift from his father during his last visit home. Where did you get the money for these? These are $200. My dad sent them, ma’am. Your dad? the way she’d said it, like she was tasting something sour.

Jame, if you’re involved in anything you shouldn’t be, you can tell me. I can help. He’d been confused then. Now he understands she thought he was selling drugs. Last month, she’d accused him of plagiarism in an essay about military strategy. This writing is too sophisticated for a seventh grader from your background.

She’d made him rewrite it during lunch, watching him the entire time, as if waiting for him to fail without Google to help him cheat. He hadn’t failed. He’d written it even better the second time because his father had taught him about the battle of Midway over summer break, walking him through tactics on their kitchen table with salt shakers as aircraft carriers.

Mrs. Henderson had given him a B minus anyway. Don’t get cocky, she’d said. The other students had noticed. Of course they had. When you’re one of seven black kids in a class of 28, everything you do gets noticed. When your teacher treats you differently, everyone sees it, even if they pretend not to.

Desawn, who sits three rows back, has gotten the same treatment. Last week, Mrs. Henderson moved him away from his lab partner, a white girl named Emma, because she said he was disrupting her learning. Deshawn hadn’t said a word during the entire class period. He’d just been sitting there existing while black. And apparently that was disruption enough.

Aisha, the only black girl in their section, stopped raising her hand in October. What’s the point? She told Jim at lunch. She never calls on me anyway, and when she does, she acts surprised when I get the answer right. But Jame had kept hoping, kept believing that if he just worked hard enough, was polite enough, perfect enough, Mrs.

Henderson would see him, really see him. The My Hero project was supposed to be his moment. 20% of their semester grade, a chance to share something real, something he was genuinely proud of. his father, General Robert Washington, a man who’d risen from an enlisted private to four-star general over 28 years. A man who’d earned a bronze star in Iraq and a Purple Heart in Afghanistan.

A man who now helped plan military strategy at the Pentagon, who’d shaken hands with three different presidents who’ dedicated his entire adult life to serving his country. Jame had watched other students present all week. Jessica Martin’s father, a financial consultant, whatever that meant. Mrs.

Henderson had called him impressive and a pillar of the community. When Jessica stumbled over her words, Mrs. Henderson smiled encouragingly. Take your time, sweetheart. Connor Walsh’s dad owned a car dealership. A small business owner, the backbone of America. Mrs. Henderson had actually applauded. Nobody questioned them. Nobody asked for proof.

Nobody demanded to see tax returns or business licenses or verification of their claims. But when Jame Washington, with his brown skin and his subsidized housing address, and his nurse mother, who worked doubles to make ends meet while his father served overseas, when he stood up and said his hero was a four-star general, Mrs.

Henderson’s entire demeanor changed. Her arms crossed, her smile vanished, her eyes narrowed with suspicion. And before he could even finish his introduction, before he could explain that his father was currently at the Pentagon for strategic planning meetings, before he could share the stories about his dad teaching him chess as a metaphor for military tactics, or the letters his father sent from deployment, or the video calls where his dad appeared exhausted, but always, always asked about James Grades first. Before any of

that, Mrs. as Henderson decided he was a liar. She’d decided it before he opened his mouth. She decided it the moment she saw the four stars on the uniform in the photo. She decided it because in her mind, people who looked like Jame, people who came from where Jame came from, people whose mothers worked as nurses instead of doctors, whose addresses included the words apartment complex instead of estate or manor.

Those people didn’t have fathers who were generals. Those people had fathers who were absent or incarcerated or working minimum wage jobs. That’s what Mrs. Henderson’s world allowed for. That’s what made sense to her. A black boy with a four-star general for a father. Impossible. Unbelievable. A lie.

So she ripped up his poster, called him a liar, accused him of committing a federal crime, humiliated him in front of 27 of his peers. And she did it with confidence, with certainty, with the full weight of her 15 years of teaching experience and her master’s degree in education and her position of authority. She did it because she could.

Because who would stop her? Principal Graves, who’d dismissed every complaint from black parents with a wave of his hand and a lecture about maintaining standards. The other teachers who’d watched her do this for years and said nothing. The parents who trusted her because she was firm and their kids got good test scores.

Nobody would stop her. Nobody ever had. Jame gathers the last piece of his father’s torn face and puts it in his pocket. His hands have stopped shaking. His jaw is set. His phone buzzes. A text from his mother. How did it go, baby? He types back with steady fingers. She called me a liar. She tore it up.

Three dots appear immediately. Then on my way. Don’t worry, baby. It’s going to be okay. Another text comes through, but this one isn’t from his mother. It’s from his father’s aid, Colonel Morrison. Someone Jame has met exactly twice. The message is short. Your mother called, “Stay strong. Help is coming.” Jame doesn’t understand what that means, but he’s about to find out. Mrs.

Henderson doesn’t let James sit down. She keeps him standing at the front of the classroom, the torn poster pieces still scattered around his feet like evidence at a crime scene. Class, pay attention to this. She walks slowly around Jame, circling him. This is a perfect teachable moment about integrity, about honesty, about consequences.

James stares straight ahead. He can feel every pair of eyes on him. Jessica Martin whispers something to Connor Walsh. They both snicker. Stolen valor. Do you all know what that means? Mrs. Henderson writes it on the whiteboard in large letters. It’s when someone lies about military service to gain respect they haven’t earned. It’s not just morally wrong.

It’s illegal. Federal crime. But I’m not lying. James voice cracks. My dad really is enough. The word comes out like a slap. Jame, I’ve been very patient with you, very understanding despite your behavioral issues this semester. I don’t have behavioral issues. Talking back to me right now, that’s a behavioral issue.

She turns to the class. You see, this is what happens when students aren’t held accountable at home. Mrs. Henderson, maybe we could just call Jame tries again. Call who? Your father the general? She laughs and several students join her. Jame, let me explain something. Four-star generals live in places like Arlington.

Their kids go to private schools. They have security details. They don’t live in River Heights apartments. The way she says his address makes it sound dirty. My mom works hard. I’m sure she does, sweetheart. The endearment sounds like an insult. She’s a nurse, correct? night shifts at Community General. That’s honorable work, but let’s be realistic.

If your father was really this highranking officer, why would she be working doubles? Why would you qualify for free lunch? Heat rushes to James face. She’s not supposed to say that out loud. The lunch program status is confidential. That’s you can’t. I’m trying to help you understand reality before you embarrass yourself further.

She pulls out a pink referral slip. I’m sending you to Principal Graves. Academic honesty violation. This isn’t fair. The words burst out before Jame can stop them. The classroom goes silent. Mrs. Henderson’s expression hardens. Excuse me. You didn’t question anyone else. Jessica’s dad, Connor<unk>’s dad, you just believed them.

You didn’t ask for proof because they weren’t making outrageous claims. How is my dad being a general more outrageous than because you have a pattern, Jame? She cuts him off, voice sharp as glass. Expensive shoes you claimed your father bought. Papers that seemed beyond your capability. Always excuses about your father’s schedule, your father’s meetings.

It’s attention-seeking behavior. She fills out the referral with aggressive pen strokes. Detention for the rest of the week. Zero on this project and a five-page essay on honesty. James phone buzzes in his pocket. He doesn’t dare check it. I want you to think carefully about your choices. Mrs. Henderson hands him the pink slip. Because if you keep lying and making excuses, you’re going to end up just like, she stops herself, swallows the rest.

But Jame heard what she didn’t say, just like all the others, just like what she expects from kids who look like him. Ms. Rodriguez appears in the doorway, her expression troubled. Patricia, can I speak with you? I’m handling my classroom. Maria, I really think you should. I said I’m handling it. Mrs. Henderson’s smile is tight. Jame, go to the office now.

Jame picks up his backpack, leaves the torn poster on the floor. 27 students watch him walk out. In the hallway, his phone buzzes again. He checks it. His mother. Baby, I’m pulling into the parking lot right now. Hold on just a little longer. Another text. This one from a number he doesn’t recognize. Jame, this is Colonel Morrison, your father’s aid. Your mother called.

Stay strong. Help is coming. Jame doesn’t understand what that means. Behind him, he hears Ms. Rodriguez’s urgent voice through the door. Patricia, you need to listen. I know this family. You don’t understand who. The classroom door closes. Jame walks toward the principal’s office, pink slip crumpled in his fist, wondering how telling the truth became a crime.

Principal Donald Graves sits behind his desk like a judge behind a bench. He’s 52, graying at the temples with the kind of face that’s perfected the art of looking concerned without actually caring. On his wall hang his credentials. Master’s degree from a state university, 15 years as an educator, awards for administrative excellence that mean nothing to the students whose complaints never make it past his door.

James sits in the chair across from him, the pink referral slip between them like a piece of evidence. Graves reads it slowly, his lips moving slightly. Then he sigh the kind of sigh that says he’s dealt with this before. That Jame is just another problem in a long line of problems. Jame. He folds his hands on the desk.

This is the third time this semester. Sir, that’s not James starts, but Graves holds up a hand. The third time you’ve been sent to my office. The third time we’ve had to have a conversation about your behavior. He taps the referral slip. Academic dishonesty, disrespect to a teacher. These are serious issues. I didn’t do anything wrong.

I was just telling the truth about my dad. Mrs. Henderson has been teaching for 15 years. She has a master’s degree in education. She knows when students are exaggerating. Graves leans back in his chair. And frankly, Jame, the story you’re telling, it doesn’t add up. What doesn’t add up? Jame feels his chest tightening.

My dad is a general. I can prove it. I can call him right now. Anyone can program a number into a phone. Then call Fort Bragg. Ask for General Robert Washington. They’ll tell you. Graves shakes his head slowly like Jame is a child who doesn’t understand how the world works. I’m not going to waste military resources on this.

Do you understand how inappropriate that would be? calling a military base to verify a student’s project. But if you just jame Graves’s voice hardens, I’m trying to help you here. I’m trying to give you a chance to be honest, to admit you exaggerated. We all do it sometimes. You wanted to impress your classmates. I understand.

But stolen valor, I’m not is a serious accusation. and continuing to insist on this story when all evidence suggests otherwise is only making things worse for you. James stares at him. What evidence? You haven’t looked at any evidence. You haven’t called anyone. You haven’t checked anything.

You just decided I’m lying. I’m looking at your file. Graves taps his computer screen. Free lunch program. Subsidized housing. Your mother works as a nurse. Night shifts. Overtime. Your father is listed as deployed. Contact information limited. These facts don’t align with having a four-star general as a parent. My mom works hard because she wants to.

My dad sends money, but she’s independent. She likes her job. James voice rises. And what does our address have to do with anything? What does free lunch have to do with my dad’s rank? Graves’s expression shifts uncomfortable now. I’m simply saying that the lifestyle of a four-star general’s family looks different than yours.

Different how? The question hangs in the air. Graves doesn’t answer it. He doesn’t have to. Jame can see it in his eyes, in the way he glances away, in the awkward clearing of his throat. Different means wealthier. Different means whiter. Different means not you. I think we need to call your mother in for a conference, Graves finally says.

And we need to discuss your placement in advanced classes. Mrs. Henderson has expressed concerns about whether you’re ready for that level of academic rigor. She wants to kick me out of AP history. Jame feels something cold settle in his stomach. Because of this, because of a pattern of behavior that suggests you might be struggling.

I have an A minus in that class. Yes. Well, Graves clicks his mouse, looking at the screen. Mrs. Henderson notes here that she suspects some of your work may not be entirely your own. The door to the main office opens. Voices drift through. One of them his mother’s, urgent and controlled. I need to see my son now.

the secretary’s nervous response. Ma’am, Principal Graves is in a meeting. I don’t care what he’s in. Get him out here. Graves stands up irritated. Excuse me, Jame. I need to handle this. He steps out of his office. Through the open door, Jame can see his mother standing in the main office. She’s still in her scrubs, her hospital badge clipped to her pocket.

Her face is calm, but her eyes are furious. Behind her stands a woman Jame doesn’t recognize, older, maybe 60, with silver hair pulled back severely. “She’s wearing a business suit that looks expensive, and she’s holding a leather portfolio.” “Mrs. Washington, I’m going to have to ask you to calm down,” Graves says using his principal voice.

“We have procedures.” “Procedures?” Sarah’s laugh is sharp. “You mean like the procedure where you investigate complaints?” because I filed three this semester alone. Three formal complaints about Mrs. Henderson’s treatment of my son. Want to know how many times you followed up? Graves glances at the secretary who’s suddenly very interested in her computer screen.

I’m sure we addressed zero. Sarah cuts him off. Zero times. Zero. I have the emails. I have the dates. I have documentation of every single complaint I filed and your responses or lack thereof. The woman with the silver hair opens her portfolio, pulls out a stack of papers. I’m Margaret Carter, attorney. I represent Mrs. Washington.

These are copies of every complaint filed by military families at this school in the past 18 months. Six families, 14 separate incidents, all involving the same teacher, all dismissed without investigation. Graves’s face pales. Now wait a minute. We are not waiting. Margaret’s voice is crisp, professional. We’re documenting. The pattern is clear.

Mrs. Henderson has targeted students from military families, particularly students of color, and you’ve enabled it by refusing to take action. That’s a serious accusation. It’s a factual statement. Margaret flips through the papers. October 15th, Major Dawson’s daughter told her father couldn’t possibly be deployed because people like that don’t serve in officer positions.

November 2nd, Sergeant Major Torres’s son, accused of cheating because his writing was too good for his demographic. December 3rd, I don’t have time for this right now. Graves interrupts. We’re in the middle of Sarah’s phone rings. She glances at the screen and something in her expression shifts. Excuse me. I need to take this.

She steps aside and Jame can hear her voice low and urgent. Yes, Dad. Yes, she did. No, they won’t listen. I know. Yes, he’s here. Okay. Okay. Thank you. She hangs up and turns back to Graves. Her face is composed now, calm in a way that’s somehow more frightening than anger. Principal Graves, I suggest you go back to your office and look up the chain of command at Fort Bragg. specifically.

Look up who the commanding general is. I don’t see why. Just do it right now. I’ll wait. Something in her tone makes Graves nervous. He retreats to his office. James still sitting there. Graves sits at his computer, types something. His face changes as he reads, then changes again. He looks up at Jame, then back at the screen.

This says, he stops, swallows. There’s a general Robert Washington listed as deputy chief of staff for strategic plans and policy. Sarah finishes from the doorway. Pentagon four stars currently in meetings with the joint chiefs. That’s my husband. That’s James father. That’s the man your teacher accused my 12-year-old son of lying about. Graves stands up slowly. Mrs.

Washington, I if I had known. You should have known. You should have checked. You should have done your job instead of assuming my son was lying because of where we live or what I do for a living or the color of our skin. The secretary knocks on the doorframe, her face white. Sir, there are there are people here, military personnel.

They’re asking for you. What? Graves looks confused. Who? Officers, sir. in uniform. They say they need to speak with you immediately regarding an incident involving a student. Margaret Carter smiles and it’s not a pleasant smile. That would be the formal inquiry. Fort Bragg takes defamation of its officers very seriously. Graves sinks back into his chair.

Jame watches his principal, the man who’s supposed to protect students, who’s supposed to be fair, who’s supposed to investigate complaints, realize that he’s made a catastrophic mistake. Where’s Mrs. Henderson? Sarah asks, her voice steady. In her classroom, the secretary whispers. Get her now. Tell her to come to the main office.

Sarah looks at Graves. You’re going to want her here for this. The secretary scurries away. Graves reaches for his phone, probably to call the superintendent, probably to cover himself. The main office door opens. Two figures in military dress uniform step through. Jame recognizes the shorter one immediately from video calls.

Lieutenant Colonel Morrison, his father’s aid. The man is 48, white with a chest full of metals and eyes that have seen combat. But it’s the second figure that makes everyone in the office stand up reflexively. Major General Patricia Hughes. Two silver stars gleaming on her shoulders. She’s 52, black, and she has the bearing of someone who’s commanded thousands of soldiers in war zones.

Principal Graves. Her voice is firm, authoritative. I’m Major General Hughes, United States Army. I’m here regarding allegations made against one of my officers. We need to talk. The main office of Jefferson Middle School has never been this quiet. The secretary has stopped typing. The attendance clerk stands frozen by the copy machine.

Even the clock on the wall seems to tick more softly, as if afraid to disturb what’s happening. Major General Hughes doesn’t sit. She stands in the center of the office like she’s standing on a command deck, and everyone else instinctively arranges themselves around her authority. Lieutenant Colonel Morrison opens his briefcase, the clicks of the latches loud in the silence.

Let me be very clear about why we’re here. Hughes’s eyes move from Graves to the secretary to Jame, and when she looks at him, her expression softens for just a moment. A teacher at this school publicly accused a 12-year-old child of committing a federal crime. She humiliated him in front of his peers. She destroyed his property and she did this based on absolutely no evidence except her own assumptions.

General, if I may, Graves starts, but Morrison pulls out a tablet and the principal’s words die in his throat. This is Jame Washington’s project poster, or what’s left of it. Morrison turns the screen to show a photo. The torn pieces laid out and photographed, each rip documented. destroyed by Mrs.

Patricia Henderson at approximately 2:15 this afternoon witnessed by 27 students, one of whom recorded the incident. He swipes to the next image. It’s a video still. Mrs. Henderson’s face frozen mid sneer, her hands holding the two halves of the poster. Do you know who this is? Morrison taps the photo on the poster.

James father in dress uniform. This is General Robert Washington. Four stars, 28 years of service. Bronze Star for Valor in Iraq. Purple Heart from Afghanistan. Currently serving as deputy chief of staff for strategic plans and policy at the Pentagon. He advises the joint chiefs. He briefs the president. Graves has gone gray.

I didn’t. We didn’t know. You didn’t check. Hugh’s voice cuts like a blade. You didn’t verify. You didn’t investigate. You just assumed a black child from a working-class neighborhood was lying about his father. Morrison swipes to another document. This is General Washington’s service record.

I’m going to read you some highlights. Enlisted at 18. Earned his commission through ROC. Ranger qualified. Airborne qualified. Served in Desert Storm Bosnia, Iraq, Afghanistan. Commanded at every level from platoon to brigade. Pentagon fellow, war college graduate, promoted to flag rank at 42, youngest in his year group. Each achievement lands like a hammer blow.

This is the man your teacher said doesn’t exist. The man she said Jame was lying about. Morrison’s jaw is tight. Mrs. Washington, would you like to add anything? Sarah steps forward. Her scrubs seem almost defiant now. A reminder that she works, that she serves her community, that she has nothing to be ashamed of.

My husband is deployed most of the year. When he’s home, we spend time together as a family. We live modestly because that’s how we choose to live. I work because I love my job, because I believe in serving others, because I’m good at what I do. Our address, our income, our lifestyle.

None of that has anything to do with my husband’s rank or my son’s truthfulness. She looks at graves and her eyes are filled with quiet fury. But you and Mrs. Henderson decided it did. You decided that because we don’t live in a mansion because I work night shifts because Jame qualifies for free lunch that he must be lying.

You decided that people who look like us, people who live where we live, can’t possibly be the families of generals. The door opens. Mrs. Henderson walks in, summoned by the secretary. She’s expecting another parent complaint, another meeting where Graves backs her up. Another situation she can dismiss with her 15 years of experience and her master’s degree.

She sees the uniforms and stops dead. Mrs. Henderson. Hughes turns to face her. I’m Major General Patricia Hughes. General Robert Washington is my direct subordinate. We work together at the Pentagon. I’ve known him for 12 years. He’s one of the finest officers I’ve ever served with. Henderson’s face drains of color.

I I didn’t You didn’t do that. You didn’t know. You didn’t bother to check. You didn’t think it mattered. Hughes takes a step closer. You told a classroom full of children that this boy was lying. You accused him of stolen valor, a federal crime. You destroyed his property. You humiliated him. And for what? I thought. Henderson’s voice shakes.

Students exaggerate sometimes. I was trying to maintain academic standards by assuming he was lying based on what? his skin color, his address, his mother’s profession. Hughes’s voice drops lower, more dangerous. Let me tell you what I think happened. I think you saw a confident black child talking about his accomplished father, and it didn’t fit your narrative.

It didn’t match your expectations. So, you decided he must be lying. Morrison pulls out another document. We requested that Fort Bragg’s JAG office review all complaints filed by military families at this school in the past 18 months. Would you like to know what they found? He doesn’t wait for an answer. Six families, four black, two Latino, all military.

One father is a major, one is a command sergeant major, one is a lieutenant colonel. All of them filed complaints about you, Mrs. Henderson. All of them documented incidents of bias, discrimination, and harassment, and all of them were dismissed by Principal Graves without investigation. Graves tries to speak, but no words come out. October 15th.

Morrison reads from the document. Major Dawson’s daughter told you her father was deployed to Germany. You said, and I quote, “People like your father don’t become officers. Are you sure he’s not enlisted? Major Dawson is a West Point graduate with two master’s degrees. Henderson’s hands are shaking now. November 2nd.

Sergeant Major Torres’s son wrote an essay about military tactics. You accused him of plagiarism because the writing was quote too sophisticated for his demographic. Sergeant Major Torres has been teaching at the Army War College for 3 years. December 3rd. Captain Morrison’s daughter. Morrison’s voice tightened slightly. My daughter wore her father’s unit patch on her backpack.

You told her it was inappropriate and confiscated it, saying she was pretending to be military. She’s a military dependent. She has every right to wear her father’s insignia. The office is completely silent except for Morrison’s voice listing incident after incident. Each one documented, each one ignored. And today, Jame Washington.

Morrison closes the folder. The final straw. Mrs. Henderson is crying now, tears streaming down her face. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. If I had known. If you had known what? Sarah’s voice is sharp. If you had known his father actually was a general, then you would have treated him with respect. That’s not how it works.

Every child deserves respect. Every child deserves to be believed until proven otherwise, not just the ones whose parents have rank. Margaret Carter, the attorney, steps forward now. She’s been quiet, documenting everything, and now she opens her portfolio. Mrs. Henderson, Principal Graves, I want to be very clear about what’s happening here.

This is not just a school disciplinary issue. This is a pattern of discrimination that has been documented and reported for 18 months. The military takes defamation of its officers seriously. The school district takes civil rights violations seriously and we will be pursuing both avenues. Graves finds his voice desperate now. Surely we can resolve this. Mrs.

Henderson will apologize. We’ll give Jame full credit for his project. We’ll you’ll do more than that. Margaret’s voice is steel voices. You’ll conduct a full investigation. You’ll review every complaint that was dismissed. You’ll implement new policies with external oversight. And you’ll both face consequences for your actions.

The main office door opens again. This time, it’s not an officer. It’s not an attorney. It’s a man in a dark suit with an earpiece. And behind him, two more men in similar attire. They step aside, forming a corridor, and through that corridor walks General Robert Washington. Four silver stars gleam on each shoulder of his dress uniform.

Ribbons cover his chest. Bronze Star, Purple Heart, Legion of Merit, Defense Superior Service Medal, Campaign Ribbons from four different conflicts. He’s 6’3, broad-shouldered with close-cropped hair graying at the temples and eyes that have commanded soldiers in combat. But when he sees Jame sitting small in the principal’s office chair, all that command presence softens.

Hey, buddy. James face crumbles. All the composure he’s held for hours breaks. Dad. He runs to his father and Washington catches him, lifts him despite the fact that Jame is 12 and almost as tall as his mother. He holds his son like he’s still small, still little. Still someone who needs protecting. I know.

Washington’s voice is gentle for Jame alone. I know, son. I heard. I’m here now. Jame is crying into his father’s uniform, shoulders shaking. She tore it up. She said I was lying. She said people like us don’t. I know what she said. Washington’s jaw tightens, but his hands are gentle on his son’s back. None of it was true.

None of it was your fault. You did nothing wrong. He sets Jame down gently, hands on his shoulders, looking him in the eye. You told the truth. You stood up for yourself. You did everything right. What she did, that’s on her, not on you. Never on you. Then he turns to face Mrs. Henderson, and the gentle father disappears.

In his place stands a four-star general who has commanded thousands of soldiers, who has made decisions in combat, who has briefed presidents and senators and foreign dignitaries. Ma’am, his voice is quiet, controlled, and absolutely terrifying. My son worships me. Do you understand what that means? He’s proud of what I do.

He tells everyone about my job because I taught him to be proud of service, proud of sacrifice, proud of doing something bigger than yourself. He takes a step closer. Henderson backs up against the wall. You took that pride and shredded it in front of his peers. You accused him of lying, of committing a federal crime, of being a liar and an attention seeker.

You humiliated a 12-year-old child because you decided based on what exactly? That he couldn’t possibly be telling the truth. General, I swear I didn’t know. Henderson’s voice breaks. You didn’t know because you didn’t check. You didn’t check because you didn’t think you needed to. You looked at my son, at his skin color, at his address, at his mother’s profession, and you decided he was lying.

That’s not a mistake. That’s bias. That’s racism. The word hangs in the air. No one moves. I’ve spent 28 years defending this country. I’ve been shot at. I’ve watched soldiers die. I’ve missed birthdays and Christmases and school plays because I was deployed. And I did it proudly because I believe in what we’re supposed to stand for. Equality. Justice.

the idea that everyone deserves respect regardless of where they come from. His voice drops lower. And then my son comes to school proud of his father wanting to share that pride. And you tell him he’s a liar. You tell him people like us don’t achieve things like this. You tell him his truth doesn’t matter. Washington pulls out his phone, swipes to a photo, holds it up.

It’s Jame at 8 years old standing in front of the Pentagon saluting. This is my son at his first Pentagon visit. He asked me that day if he could be a general, too. I told him he could be anything he worked for, anything he dreamed of. I told him the world was open to him. He lowers the phone. And you tried to close that world.

You tried to teach him that his dreams don’t matter, that his truth will be questioned, that people will doubt him because of how he looks. Well, I’m here to teach him something else. He turns to Jame. Son, look at me. Jame wipes his eyes, looks up at his father. People will doubt you. Not everyone, but some people.

They’ll doubt you because of your skin color, because of where you’re from, because of assumptions they make before you even open your mouth. Washington kneels down eye to eye with his son. That’s their failure, not yours. You hold your head up, you tell your truth, you let them be wrong, and you keep moving forward. He reaches into his briefcase, pulls out a poster, professionally printed, laminated, beautiful.

It’s his official Pentagon photo. Four stars gleaming with the Department of Defense seal in the corner at the bottom in an elegant script. General Robert Washington, United States Army, Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategic Plans and Policy for your project. He hands it to Jame. I expect an A. James takes it with shaking hands, staring at the poster like it’s made of gold.

Washington stands, turns back to Henderson and Graves. Now, let’s discuss the consequences. The next morning, Jefferson Middle School feels different. Word has spread overnight through text messages, social media, parent group chats. By the time the first bell rings, everyone knows what happened. Everyone knows Mrs.

Henderson is gone. Everyone knows why. Jame walks through the front doors with his mother and father on either side of him. Students stop in the hallways staring. Some whisper. Some pull out their phones. But this time, Jame doesn’t look down. He holds his head up just like his father taught him. Principal Graves’s office is dark.

His name plate has been removed from the door. In his place, a woman named Dr. Patricia Foster sits behind the desk. interim principal sent by the district superintendent at 6:00 this morning. She’s 53, black, a former military herself. She stands when the Washingtons enter. General Mrs. Washington Jame. She shakes each of their hands.

I want to apologize on behalf of this school district for what happened to your son. That’s unacceptable. Apologies are a start, Sarah says quietly. But we need to see real change. You will. Dr. Foster pulls out a folder. The school board met in an emergency session last night. Mrs. Henderson’s contract has been terminated.

Her teaching license is under review by the state. She will not teach again in this district. She looks at Jame. Your project grade has been changed to A+. Miss Rodriguez has agreed to take over the AP history class. Principal Graves is on permanent administrative leave. Every dismissed complaint is being reinvestigated.

Dr. Foster closes the folder. And starting today, every complaint will be logged with the district office. Every complaint will be investigated within 48 hours. What about the other students? General Washington asks. The ones who witnessed what happened. What are you teaching them now? Dr. Foster meets his eyes.

That’s why you’re here. I’d like you to speak to James class. Room 204 looks different when Jame walks in at 10:00. Ms. Rodriguez stands at the front, smiling warmly. The students are already seated, quieter than usual. Deshaawn catches James eye and nods. Aisha gives him a small wave. Even Jessica and Connor look uncomfortable, guilty.

Then General Washington walks in and every student stands up reflexively. When a four-star general enters a room, you stand. Please sit down. Washington’s voice is gentle but carries authority. He walks to the front and James sits in his usual seat. My name is General Robert Washington. I’m James father and I’m here because something happened in this room yesterday that should never happen anywhere.

He doesn’t pace. He doesn’t lecture. He just stands there and talks to them like they’re adults. How many of you believe James was lying? He waits. Slowly, five hands go up, then seven, then 10. Thank you for being honest. Why did you think he was lying? Connor speaks first, his voice small. Because generals are supposed to be really important and Jame is just normal.

Normal, Washington repeats. What does that mean? Connor squirms. Regular. You mean poor? Washington says flatly. You mean black. You don’t like what you think important people look like. The classroom is silent. Let me tell you something. Important people come from everywhere. They look like everyone.

Some of the best soldiers I commanded grew up in places like James neighborhood. Some had mothers who worked three jobs. Some qualified for free lunch. He pauses. Some of them were me. He lets that sink in. I grew up in Detroit. My mother cleaned houses. My father left when I was six. We lived in a two-bedroom apartment. My mom, my grandmother, three siblings, and me. I got a free lunch.

And when I told my seventh grade teacher I wanted to join the military, you know what he said? The students lean forward. He said people like me ended up in jail, not in uniform. He said I should lower my expectations. Know my place. What did you do? Aisha asks quietly. I proved him wrong. I enlisted at 18, earned my degree while serving, got my commission, worked harder than everyone around me because I had to be because people were always assuming I didn’t belong.

He looks at Jame and now my son has to do the same thing. Jessica raises her hand. General Washington, I laughed yesterday when Mrs. Henderson tore up the poster. I’m really sorry. Why did you laugh? because everyone else was laughing. Because I didn’t know what else to do. Washington noded slowly. That’s honest and that’s the problem.

When you see injustice and you laugh because everyone else is laughing, you become part of the injustice. When you stay silent because it’s easier, you’re not neutral. You’re choosing a side. He looks around the room. Some of you stayed silent yesterday. Some laughed, but the three of you did something different. He points to Deshaawn.

You recorded it. That recording is now evidence. He points to Aisha. You texted your mother who’s on the school board. You used your voice. He looks at Jake. And you gave a written statement after school. Even though you were scared. Jake’s eyes are red. I should have said something during class.

Yes, you should have. But you said something after. That matters, too. The question is, what will you do next time? He walks to the board, picks up a marker, writes three words. See, speak, stand. When you see injustice, speak up. When you speak up, stand firm. Even when it’s hard. Even when adults are the ones being unjust.

Ms. Rodriguez steps forward. What happened yesterday wasn’t just mean, it was racism. That word makes people uncomfortable, but we need to say it. Mrs. Henderson treated Jame differently because of the color of his skin. That’s racism. It exists in this school. Pretending it doesn’t make it go away. General Washington hands Jame the new poster. Laminated, official, perfect.

Son, why don’t you finish your presentation? James stands, walks to the front, holds up the poster, and this time when he talks about his father, about deployments, medals, service, no one interrupts, no one laughs, no one questions. When he finishes, Deshawn starts clapping. then Aisha, then Jake, then the whole class stands applauding.

Jame looks at his father and General Washington nods once proud. That afternoon, the school holds an assembly. Dr. Foster announces new policies, military family liaison position, bias training for all staff, external oversight committee, and she announces something else. The hallway outside room 204 will be called the Hall of Heroes.

James poster will be the first to be mounted there. Any student who wants to honor a family member who serves can submit a poster because heroes come from everywhere and no one should ever be told their truth is a lie. 6 months later, Jame Washington walks through the same hallways of Jefferson Middle School, but everything has changed.

The Hall of Heroes stretches along the entire second floor corridor now. 43 posters line the walls. Firefighters, nurses, police officers, soldiers, faces of every color. And right at the center hangs his father’s poster. Four stars gleaming, a reminder. Miz Rodriguez’s AP history class has doubled in size. Students who were told they weren’t ready are thriving now.

Deshawn got an A on his last essay. Aisha raises her hand in every class. Jame is at the top of his grade. Mrs. Henderson never taught again. Her license was revoked. Principal Graves works in insurance now. Dr. Foster became permanent principal. Under her leadership, disciplinary referrals for black students dropped 64%. Not because students changed, because the system did.

The video, the one Deshaawn recorded, went viral, 4.2 million views. News outlets everywhere. The hashtag #belie black children trended for 3 days. Parents everywhere started sharing similar stories. Teachers who questioned black students achievements. Administrators who dismissed complaints. Systems that protected bias instead of children.

The Department of Education investigated Jefferson School District. They found patterns spanning years affecting dozens of families. The district overhauled policies, retrained staff, and implemented real oversight. Other schools watched. Other districts took note. Change spreads. General Washington was promoted.

His fourth star became official at the Pentagon, and James stood beside him in a cadet uniform. He’d joined JOTC, following his father’s path, carving his own. A reporter asked Jame. I learned that my truth matters, even when people don’t believe it. I learned that staying silent makes you part of the problem.

And I learned that change doesn’t come from people with power. It comes from people who refuse to accept injustice. What would you say to other kids going through something similar? Jame looked at the camera. Document everything. Tell someone who will listen. Don’t let them make you doubt yourself. And remember, just because someone has authority doesn’t mean they’re right.

But here’s the truth that makes people uncomfortable. James father had rank. Four stars on his shoulders. He could walk into that school with generals and attorneys and people had to listen. But what about the thousands of black children whose parents aren’t generals? Whose fathers don’t have stars or medals or power to demand accountability? Whose mothers work night shifts and can’t afford attorneys.

Their truth matters just as much. Their dignity deserves just as much protection. The real question isn’t what would have happened if James father was a general. The real question is what happens when he’s not. That’s where the rest of us come in. You don’t need to be a four-star general to make a difference.

You need to be willing to see injustice when it happens. To record it like Deshawn, to speak up like Aisha, to give statements like Jake even when it’s scary. You need to believe children when they tell their truth. To investigate complaints instead of dismissing them. To hold systems accountable. You need to be someone’s General Washington, someone’s Deshawn, someone’s Ms. Rodriguez.

Because right now, somewhere in a classroom, another Jame is standing at the front of the room. Another teacher is looking at them with doubt. Another moment of injustice is unfolding. And that child is waiting for someone, anyone, to believe them. Will it be you? Have you ever witnessed a moment like James? A time when someone’s truth was dismissed because of how they looked, where they lived, what people assumed.

Did you speak up or did you stay silent? The next Jame is in a classroom right now. The next Mrs. Henderson is making assumptions right now. The next Principal Graves is dismissing a complaint right now. Be the person who changes the story. Share this if you believe every child deserves to be heard. Share this if you believe black children’s truth matters.

Share this if you’re ready to be part of the change. Because heroes don’t just wear four stars. Sometimes they just wear the courage to say this is wrong and I won’t be silent anymore. That’s why believe black children every truth matters to justice for Jame. James got his justice. His father walked into with four stars on his shoulders.

And Mrs. Henderson lost everything. But here’s the part that keeps me up at night. James had a fourstar general for a father. What about the kids who don’t? Before Jane, there were 11 other families. 11 complaints were filed against Mrs. Henderson. All ignored, all buried. Six military families document the exact same pattern.

Black and brown children being told their truth didn’t matter. And principal graves dismissed every single one. Not because there was an evidence because no one with enough power is force forcing him to look. James father had rank. He had stars. He had generals walking in behind him. That’s why people listened. But think about that for a second.

A 12year-old child had to have fourstar general prove he wasn’t lying just to be treated with basic respect. How many classrooms right now have a James standing at the front? A kid telling the truth while a teacher decides it doesn’t fit their expectations. And how many of those kids have the someone powerful enough to walk through that door and demand accountability? Most don’t.

Most just walk with their torn papers, poster, their dignity stranded, believing maybe they were wrong to speak up at all. That’s the real tragedy, not what happened to Jane. But what’s happening right now to the children is nobody’s recording. You don’t need four stars to make a difference. Desawn hit a record that mattered. I just woke up. That mattered.

You can be the person who doesn’t laugh when everyone else does, who records, who report, who refuses to let it slide. If this story made you angry, share it. Subscribe to Black Legacy and tell me in the comments, have you ever been the kid whose truth wasn’t believed? Or have you been the person who stayed silent when you should have spoken because the next game is in a classroom right now and they’re waiting for someone to believe them.

Leave a Reply